The Archaeological Site of

ISTHMIA

(July 2022)

Isthmia (Ίσθμια) is an ancient sanctuary of Poseidon and an important archaeological site and museum on the Isthmus of Corinth. Situated on the territory of the ancient city-state of Corinth (Κόρινθος), it was famous in antiquity for the Isthmian Games and its Temple of Poseidon.

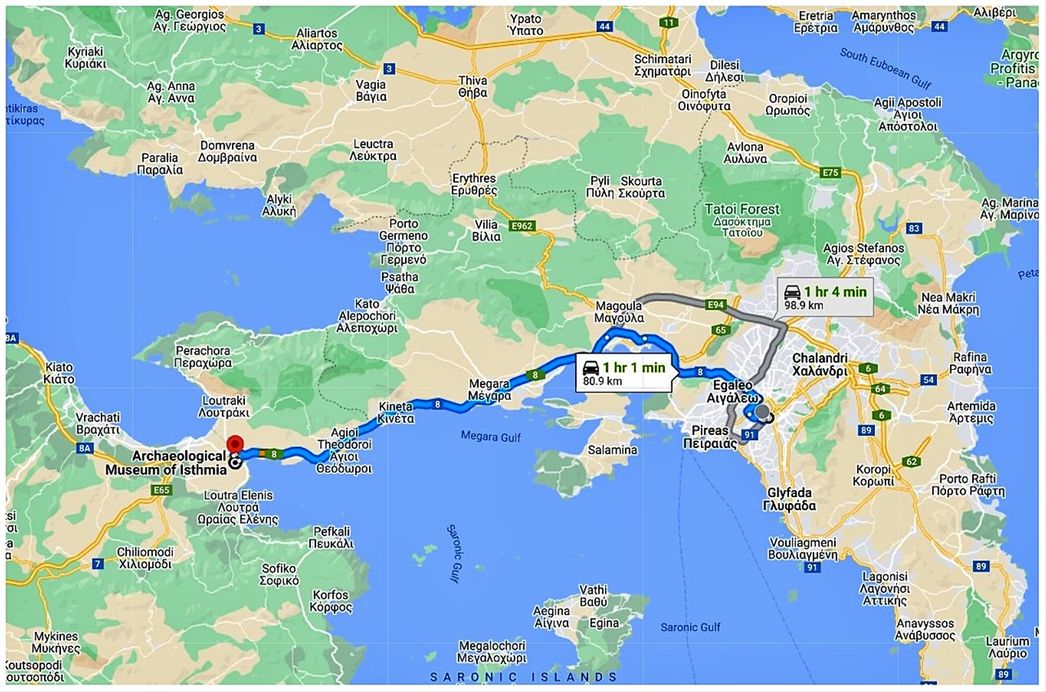

The site can be easily reached from Athens in just one hour on a car following Olympia Odos (the Motorway connecting Athens to Peloponnese). To reach the archeaological site, just after the Corinth Canal, leave the Motorway on Exit 10, follow the EO "Isthmou Archaias Epidavrou", and then turn right onto EO "Gefiras Isthmou - Isthmion". The building of the museum is on the right. There is a small parking lot outside the museum.

The archaeological site of Isthmia is located only one hour drive from central Athens.

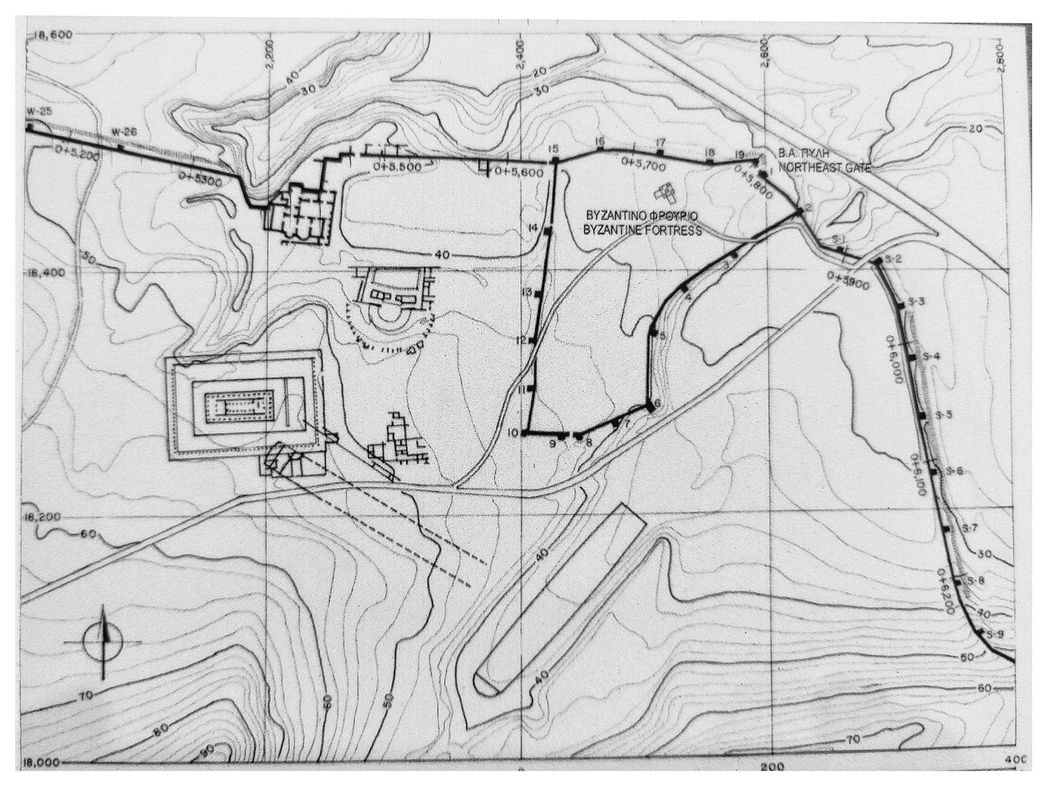

The Geographical Position Of The Sanctuary

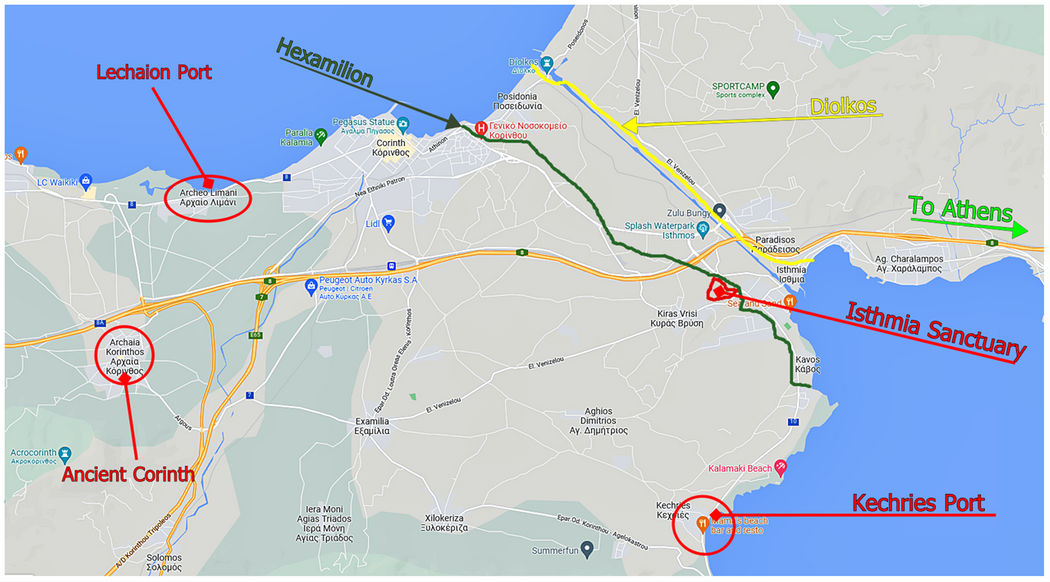

Isthmia is located on the critical land route connecting Athens and central Greece with Corinth and the Peloponnese. Its location on the Isthmus, between the two Corinthian ports of Lechaeum (Λέχαιο) on the Gulf of Corinth and Kechries (Κεχριές) on the Saronic Gulf, made Isthmia a natural site for the worship of Poseidon, god of the sea and also of mariners.

Isthmia sits on a very active fault line, and Poseidon's role as "Earth-holder" in causing and averting earthquakes is another reason Isthmia became the center of athletic and religious festivals in his honor. The Games at Isthmia were second in significance only to those at Olympia.

The narrow ribbon of land throughout the ages functioned as a political and commercial meeting place: the diolkos (διολκός), or paved roadway, between the Corinthian and Saronic gulfs, reveals the importance of the place for transport of men and goods.

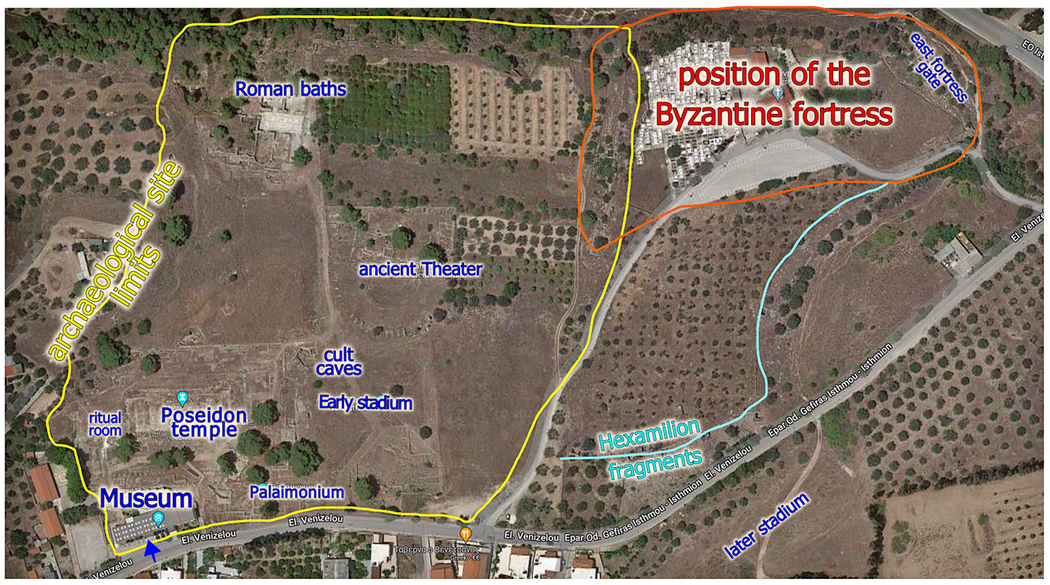

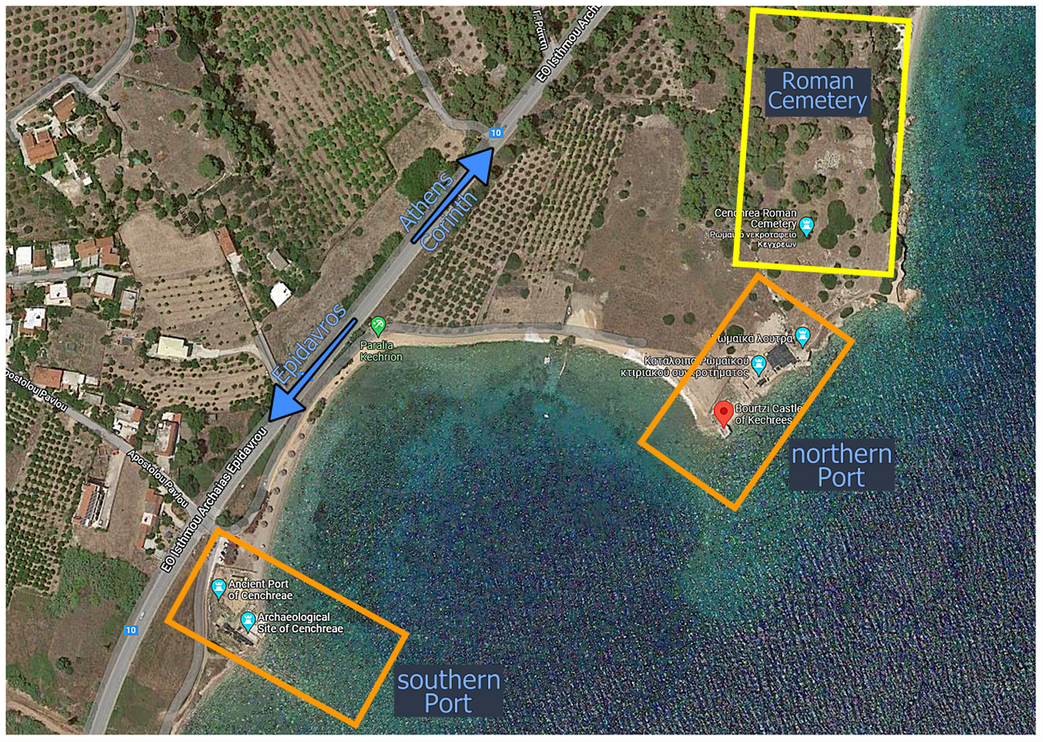

Local map of Isthmia and the area around it.

The Isthmus (Ισθμός) was a place where attempts were made to halt invasions from the North by constructing walls. The Classical and Hellenistic barriers did not extend across the entire Isthmus, but the Hexamilion (εξαμίλιον) built in Byzantine times went from sea to sea.

The Temple of Poseidon (center of the Isthmia Sanctuary) stands on a plateau 1.5km from the Saronic gulf, 16km from the Corinthian gulf, and immediately north of a low ridge named the Rachi (Ράχη) locally. The road connecting Corinth with the Isthmus passed along the north side of the plateau.

During the Classical and Hellenistic periods, the plateau's surface was extended by terracing to the North and east sides to accommodate the ever-larger crowds attracted to the popular games.

The Sanctuary extended from the central temple for about 560 meters to the west, reaching as far as another, more prominent gully (the Kyras Vrisi Gorge). In the gully were shrines to Demeter & Kore, Dionysus, and other deities. The area, known as the "Sacred Glen", was supplied by a spring from which water was piped to the temple, theater, and other places to the east.

The Sanctuary was the most significant shrine outside the walls of the city of Corinth. Sacrifices and feasting began in the mid-11th century BC. Small dedications and tripods were added three centuries later.

In the 7th century, the festival of Poseidon became PanHellenic and followed the Olympic model with athletic and equestrian competitions every two years. After the Romans sacked Corinth in 146 BC, the games moved to Sikyon, returning to Corinth with the foundation of the Roman colony a century later. The first Temple of Poseidon and the altar were completed by 650 BC. A great fire destroyed the archaic temple in the mid-fifth century BC, and immediately in the same place, a second, more prominent temple in the Classical Doric order was constructed. The foundations are visible today. In Roman times the temple was enclosed by four long stoas, and a shrine to the hero Melikertes-Palaemon was added.

The Corinthians built a stadium southeast of the temple, but with increased spectators in the Hellenistic period, they made a new and larger stadium further southeast.

At the foot of the plateau was a Greek bathing establishment, which was replaced in Roman times by a larger bath building. To the east of the bath, the Greeks located their theater which continued there throughout the Roman period. The theater used for musical contests. The end of the Sanctuary came shortly after 400 AD in the wake of Alaric's invasion. The buildings were dismantled to build a defensive wall across the Isthmus and a fortress at the east end, which we see today.

History

Archaic, classical & Hellenistic periods

As Greece moved into the Archaic period, writing, material culture, and population increased. The people of Isthmia began constructing significant stone monuments and religious sanctuaries. In the year 481 BC, the Persian Empire attempted to invade Greece. Isthmia was not a significant battlefield, but its central location made it a preferred site for Greek conferences and pre-battle meetings. The Archaic temple at Isthmia was severely burned in a fire in 480 BC, and the Doric-style temple built later at its place. In 390 BC, during the Corinthian War, the Spartan king Agesilaus encamped at the sanctuary, and the temple of Poseidon was burned down in uncertain circumstances. The lack of pottery found at the site after the fire indicates that Isthmia entered a period of decreased prosperity at this time. After Philip II, King of Macedon won the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BC, and he united the Greek city-states into the League of Corinth, which was formed at a council at Isthmia. Philip's successor, Alexander the Great, called a meeting in Isthmia between the Greek city-states to discuss his war with Persia. During the Wars of the Succession after Alexander's death, several successors tried to use Isthmia as a central place in short-lived attempts to unify the Greeks under their control - first Ptolemy I in 308 BC and then Demetrius Poliorcetes. The latter refounded the League of Corinth at Isthmia in 302 BC.

Roman era

A permanent settlement was established on the Rachi hill to the south of the temple at the end of the fourth century BC. This settlement lasted until it was destroyed by the Roman Republic in 198 BC, during the Second Macedonian War. After the Romans defeated Macedonians in that war, Titus Quinctius Flamininus declared the "Freedom of the Greeks" at Isthmia, cementing the location's status as a symbol of Greek unity and freedom. In 146 BC, rising tensions between the Greek states and the increasingly hegemonic Romans resulted in a last attempt by the Achaean League to maintain its independence. The Achaean War ended in a quick Roman victory, and consul Lucius Mummius Achaicus ordered the destruction of Corinth as an example to all Greeks. The sanctuary was destroyed, and control of the Isthmian Games was transferred to Sikyon (near modern kiato). The Isthmian Games were returned to Corinth after its foundation as a Roman colony by Julius Caesar in 44 BC. However, it appears that the games were held in Corinth, and there is little evidence of activity at Isthmia until the mid-first century AD. Emperor Nero visited the site on his tour of Greece in AD 67 and performed in the musical events at the Isthmian Games. A new round of construction in the second century AD was presided over by the local aristocrat, Licinius Priscus Juventianus.

Late Antique, Medieval, and Early Modern periods.

In the 4th century AD, Emperor Constantine the Great banned all pagan religions and artifacts from Isthmia. The Temple of Poseidon fell into disuse, and its material was partly re-used for the building of the Hexamilion wall, which was used as protection against invading barbarians in the 5th century. The Ottoman Empire captured Isthmia in 1423 and permanently in 1458. Isthmia was fought over by the Turks, Venetians, and local potentates for over three centuries. In 1715, the Venetians were expelled, and the Ottoman Empire controlled southern Greece for a hundred years until the Greek War of Independence.

History of the Isthmia Excavations

The first systematic archaeological investigation under Paul Monceaux of the French School in Athens took place in 1883 in the area of the Byzantine fortress, which was thought then to represent the Sanctuary of Poseidon.

The theory was disproved by the British archaeologists R.J.H. Jenkins and A.H.S. Megaw in the early 1930s. Still, the discovery of the Temple of Poseidon came only in 1952 when Oscar Broneer began systematic excavations for the University of Chicago under the American School of Classical Studies at Athens.

He excavated the temple, the theater, two caves used for dining, the central part of the sanctuary with the Early Stadium, the Palaimonion, and the Rachi Settlement, and he explored outlying monuments, including the Later Stadium. Broneer's findings were published in three volumes starting in 1971 and articles in the Hesperia Journal.

In 1967 Paul Clement began excavating the Roman Bath for the University of California at Los Angeles. He continued until 1987, uncovering portions of the Trans-Isthmian Wall (the 'Hexamilion'), the fortress, and the area east of the main temple (East Field). He was succeeded by Timothy E. Gregory of Ohio State University in 1987, who was himself succeeded by Jon Frey of Michigan State University in 2020. These excavations focused mainly on the Roman bathing complex and the Byzantine fortress.

Elizabeth Gebhard took over the University of Chicago finds management from Oscar Broneer in 1976. Between August 16 and November 29, 1989, she led new excavations in the central area of the sanctuary under the auspices of the University of Chicago, primarily to clear up disputes that had arisen over the conclusions Broneer had drawn from his finds. The first report of the 1989 findings was published in Hesperia in 1992, with subsequent reports in later years.

These excavations helped to uncover evidence relating to all the areas of development of Isthmia from the Bronze Age to the Roman period, but in particular focused on the Archaic temple, partly because this is the most complete of the buildings found at the site despite being one of the oldest.

The Isthmian Games

Isthmian Games or Isthmia (Ἴσθμια) were one of the Panhellenic Games of Ancient Greece and were named after the Isthmus of Corinth, where they were held. As with the Nemean Games, the Isthmian Games were held both the year before and the year after the Olympic Games (the second and fourth years of an Olympiad), while the Pythian Games were held in the third year of the Olympiad cycle.

The Games were reputed to have originated as funeral games for Melicertes (also known as Palaemon), instituted by Sisyphus, legendary founder and king of Corinth, who discovered the dead body and buried it subsequently on the Isthmus.

In Roman times, Melicertes was worshipped in the region. Another likely later myth held that Theseus, legendary king of Athens, expanded Melicertes' funeral games from a closed nightly rite into the fully-fledged athletic-games event which was dedicated to Poseidon, open to all Greeks, and was at a suitable level of advancement and popularity to rival those in Olympia, which Heracles founded. Theseus arranged with the Corinthians for any Athenian visitors to the Isthmian games to be granted the privilege of front seats.

The first Isthmian Games were held in 582 BC. The festival included athletic and musical competitions. The Isthmian games were used by many as a forum for political propaganda.

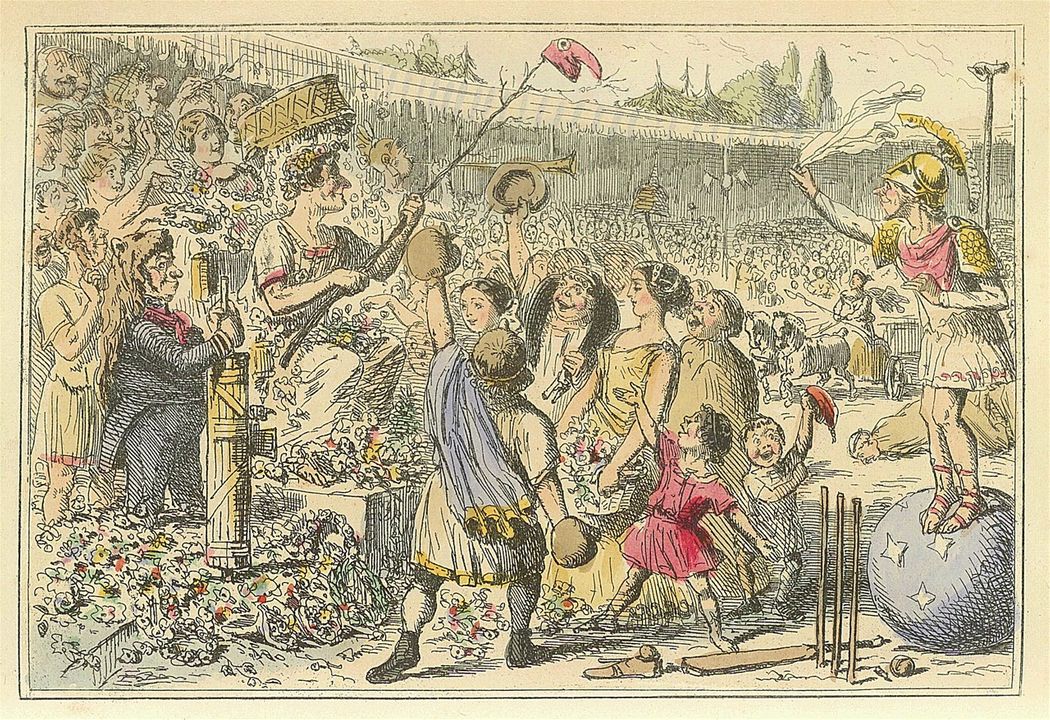

These were stephanite games (i.e., with a crown as a prize), and at least until the 5th century BC (Pindar's time), the winners of the Isthmian games received a wreath of celery; later, the wreath was altered such that it consisted of pine leaves and called Isthmian pine (Ἰσθμική πίτυς). Victors could also be honored with a statue or an ode. Besides these prizes of honor, the city of Athens awarded victorious Athenians with 100 drachmas. From 228 BC or 229 BC onwards, the Romans were allowed to participate in the games. In 196 BC Titus Quinctius Flamininus used the occasion of the games to proclaim the freedom of the Greek states from Macedonian hegemony.

Image by John Leech, from: The Comic History of Rome by Gilbert Abbott A Beckett. Bradbury, Evans & Co, London, 1850s Flaminius restoring Liberty to Greece at the Isthmian Games.

Since the games' inception, Corinth had always been in control of them. When Corinth was destroyed by the Romans in 146 BC, the Isthmian games continued, but were now administered by Sikyon. Corinth was rebuilt by Caesar in 44 BC, and recovered ownership of the Games shortly thereafter, but they were then held in Corinth. They did not return to the Isthmus until AD 42 or 43. Libanius mentions the continuation of cultic activities at the Isthmus into the middle of the 4th century, and the games probably continued at least until the end of that century. The circumstances of their demise are unknown. Imperial pressure against pagan rituals was heightened at the end of the 4th century, but some polytheistic cult practices certainly continued at Corinth into the 6th century.

This coin commemorates the Isthmian Games in the Spring 66 or 67 AD, held at Korinthos (Isthmus of Corinth) in honor of Poseidon. Front: radiate bust of Nero, wearing aegis. Back: ust of Poseidon Isthmios to right, wearing taenia, with slight drapery on his left shoulder and with trident over his shoulder.

The games were the same as those in Olympia, including among other competitions: Chariot races (men only), Pankration (men only), Wrestling (men only), Musical and poetical contests (women were allowed to compete), Boxing (men only).

THE MUSEUM

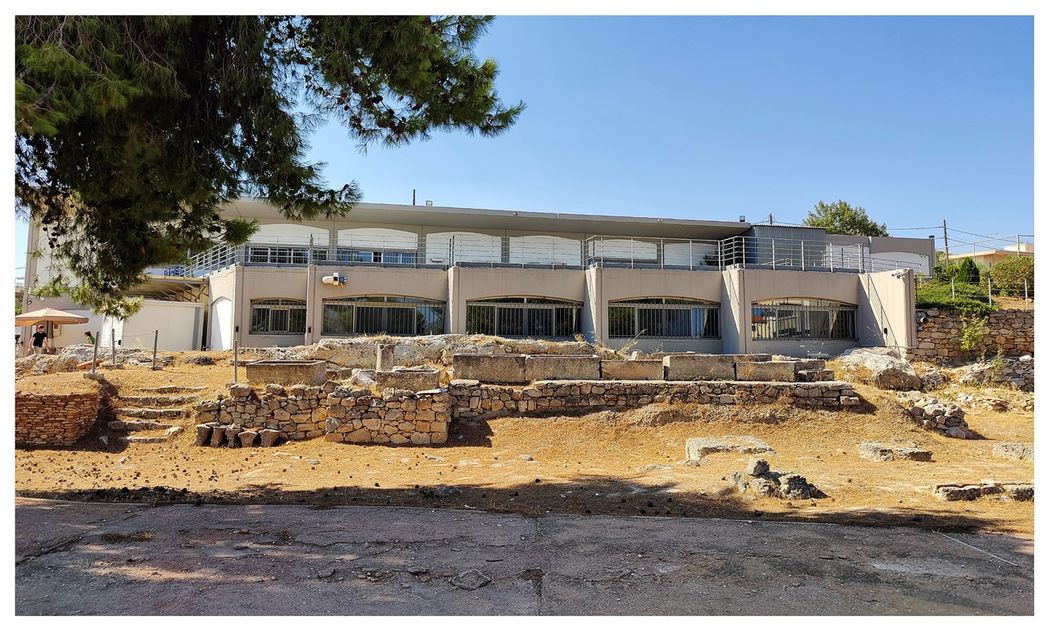

The museum is a small construction built in 1970 by the architect Paul Mylonas and opened to the public in 1978. It is built next to the Archaeological site of the pan-Hellenic sanctuary of Poseidon, the entrance of which is through the museum building.

Besides its size, the museum is quite impressive. Still, unfortunately, it remains relatively unknown as it is overshadowed by other essential places of archaeological and historical interest in the surrounding area.

The museum contains collections of finds from the sanctuary of Poseidon, the sanctuary of Palaemon, the Hellenistic settlement at Rachi, and the excavations in the area of Isthmia and the ancient harbor of Kechries.

Entrance fee: €3, €2 (reduced)

The entrance to the museum building.

The museum building (back side) as seen from the archaeological site.

The building consists of a vestibule and one large room. Individual finds, sculptures, epic columns, and part of the simi of the temple of the 4th century BC are exhibited in the vestibule of the Museum.

(Bellow left) Victor's stele with portrait of Komelios the Corinthian. According to the architrave inscription the monument was dedicated by two sons, the Komelios Korinthos and the Komelios Sabeinos in honor of their father Loukios Komelios Korinthos who was successful in many musical competitions. (bellow right) Victor's stele. The victories of the unknown athlete (his name is not preserved) are recorded by inscriptions within the carved wreaths. (top) Detail of the Komelios' stele.

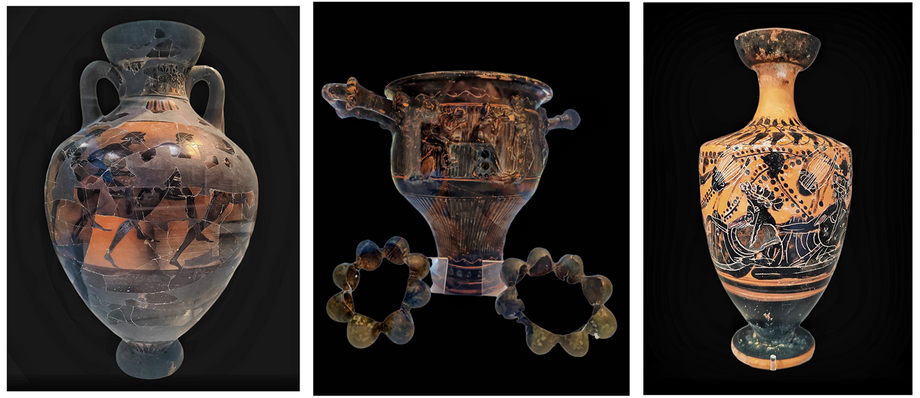

The main hall is divided into 2 sections: a) the sanctuary and the wider area, and (b) the port of Kechries, where parts of the unique glazing are exhibited. Also, parts of the tiling and the frescoes of the Archaic temple, a marble trunk of Amphitrite from the cult constitution of the temple of the Roman period, an elaborate marble enclosure of the 7th c., etc. Findings related to the competitions of the Isthmian Games (dumbbells, iron disc, staves, chariot wheel section, etc.), as well as chronological findings of the various phases of worship of Melikertis. Also, supervisory material related to the construction and operation phases of the ancient theater-conservatory of the sanctuary of Isthmia and findings from the interior of a worship cave of the 4th c. BC, as well as commercial amphorae from the classical to the Byzantine period from various places in the region of Isthmia, accompanied by supervisory material related to trade and ancient Diolkos. Finally, one can see material related to the luxurious Roman baths.

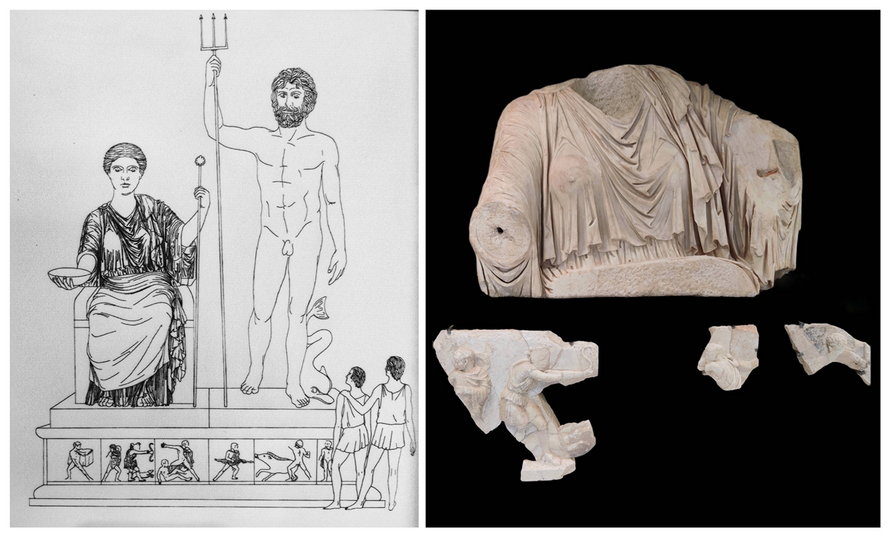

THE COLOSSAL CULT STATUE GROUP of THE TEMPLE OF POSEIDON The cult statue group was composed of a nude Poseidon with his consort Amphitrite seated on a throne, as shown in the restored drawing. The colossal female torso is approximately 3 times life size; most of Poseidon is lost. The artistry is of excellent quality, and these sculptures were probably made by Attic artisans using Pentelic marble. Panels with relief sculptures were mounted on the base of the cult statue group. The Calydonian boar hunt, which includes Atalanta with her bow, was represented. The other subject, the slaughter of the Niobids, expresses a warning against hubris and foul play. At Olympia, such warnings were directed toward athletes who might be tempted to cheat at the games. The statue group and base belong to the Antonine period (2 c. AD).

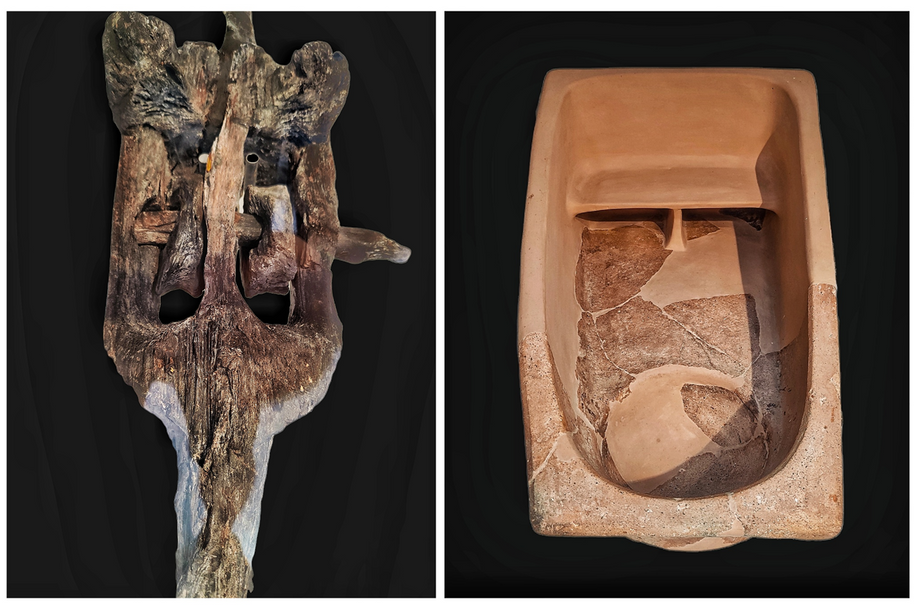

Double-sheaved pulley block. Found in association with a series of opus sectile panels.(left). Terracotta bath tab from Rachi settlement. Hellenistic period. (right).

Ceramics found in and around the sanctuary (left). Trade and transport amphoras (right).

Hercules and the Nemean Lion. A statuary group, used as a fountain sculpture. Found south of the theater. c.150AD. (middle) Portrait of Polydeukes from the Roman Baths. c.150 AD. (right) Head of athlet.

In the section of the port of Kechries located at the western end of the room, findings from the partly underwater excavations at the two piers of the ancient port and the Roman necropolis of Rahi Koutsogilla located just north of the port are exhibited.

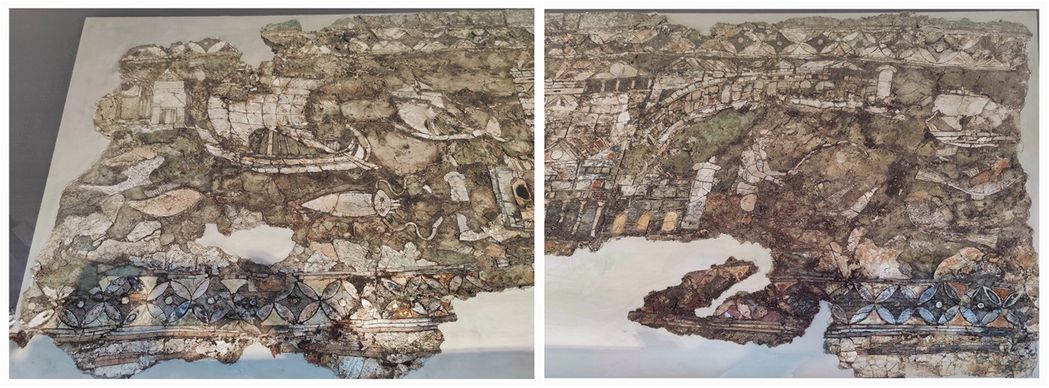

From the port of Kechries, there are exposed sections of unique glazing in their kind. Glass panes are a form of glass mosaics of the 4th century AD. They were discovered in the American School of Classical Studies excavations in 1964-1968. They were packed (every two face to face) in wooden crates stacked on the floor of a seaside building.

Glass panes from Kechries.

In the main hall, it is worth admiring the 7th-century BC archaic marble basin (perirrhanterion) supported on an elaborate stand. The bowl, 1.24 m. in diameter, rests on a ring supported by four women, each standing on the back of a lion and holding in one hand the lion's leash and in the other its tail. The ring between the women is decorated with rams' heads. The exquisite stone carving was further embellished by paint on the figures' hair, face, and clothing. The worn surfaces of its handles and rim bear witness to the people that reached into it, presumably for water to purify themselves before entering the inner chamber. The carving style makes the monument contemporary with the temple or a little later. The circular base can still be seen outside the pronaos of the Archaic Temple. Although basins of this type were popular in the seventh century, the Isthmian perirrhanterion is outstanding in the intricacy of its design and quality of execution. We can safely conclude that it was a significant dedication to Poseidon given by a person or family of high prestige and wealth.

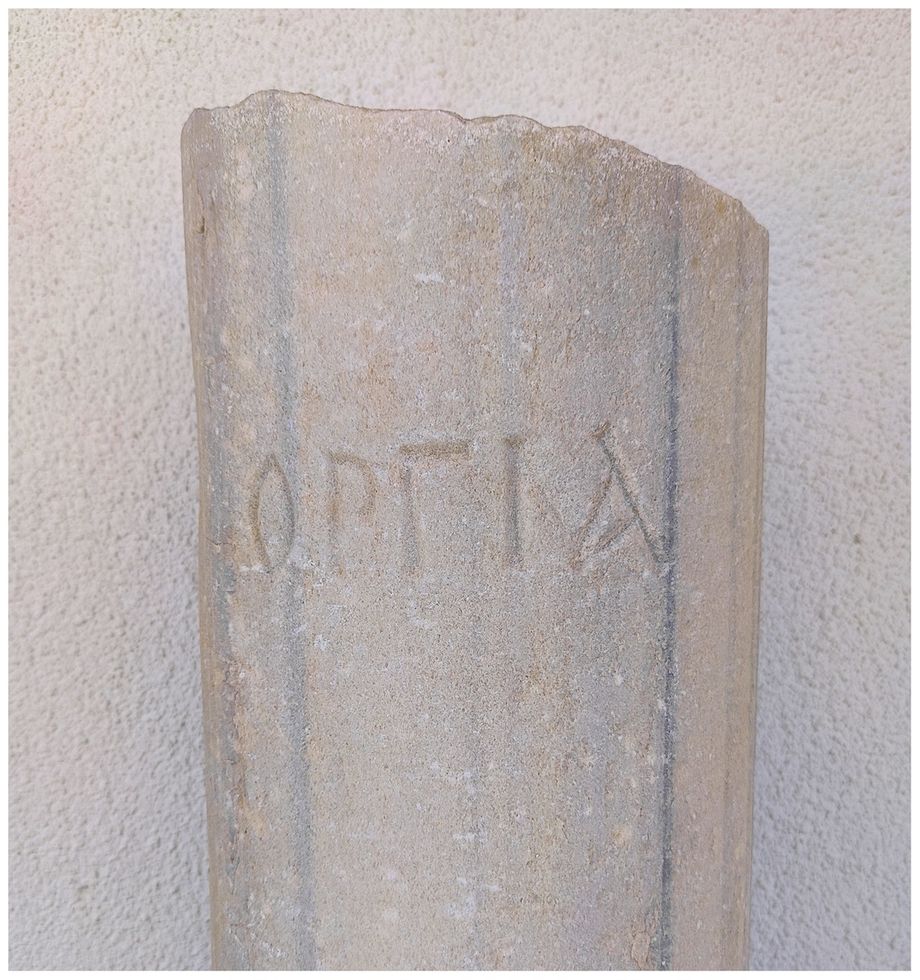

An inscribed column with the Greek word “Ὀργία”; literally referring to secret rights or mysteries. This word is interpreted as being an epithet of Isis and was also used by Plutarch to specifically describe the mysteries of Isis and Osiris. It was found at Kechries port.

THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITE

The Temple of Poseidon

Around the turn of the 8th to 7th century BC, it is apparent that a new period emerged in both Greek architectural and artistic history. Corinth was at the center of this with its development of new pottery design, settlement planning, military organization, and most significant, being the possible birthplace of monumental buildings and a new style of architecture known as the Doric order. The date of the Archaic (*) Temple of Poseidon construction in Isthmia is essential as it was established when monumental architecture began and when the transition from Iron Age architecture to Doric occurred. This was also the point where the Greek temple as a whole became a defined form.

(*) Archaic Greece was the period in Greek history lasting from circa 800 BC to the second Persian invasion of Greece in 480 BC, following the Greek Dark Ages and succeeded by the Classical period. In the archaic period, Greeks settled across the Mediterranean and the Black Sea, as far as Marseille in the west and Trapezus (Trebizond) in the east. By the end of the archaic period, they were part of a trade network spanned the Mediterranean.

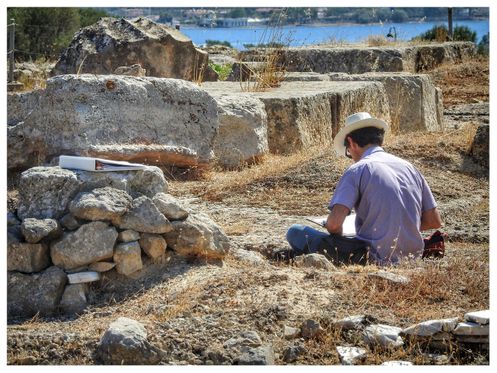

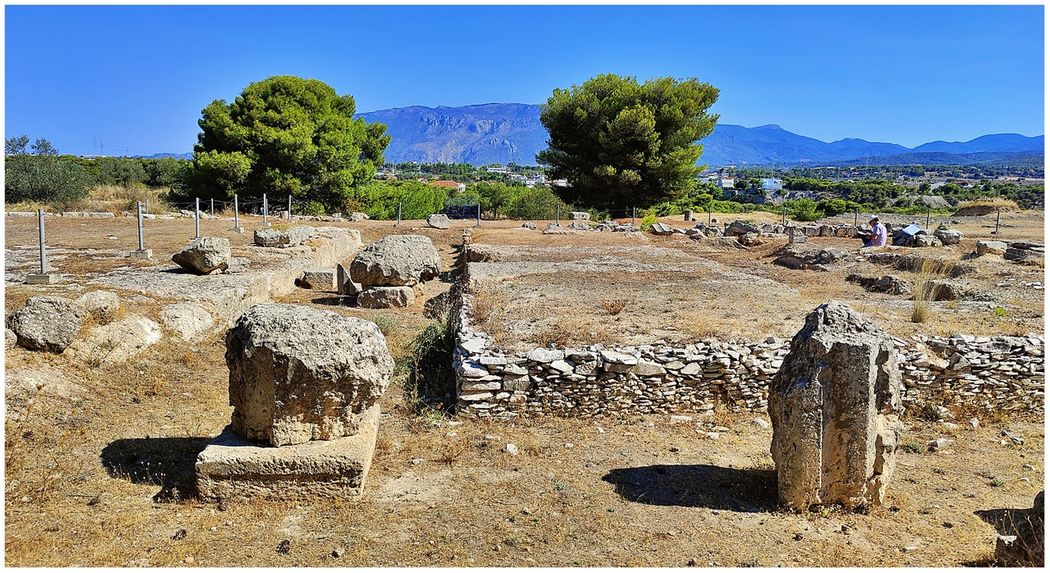

An archeologist working inside of what used to be the temple of Poseidon.

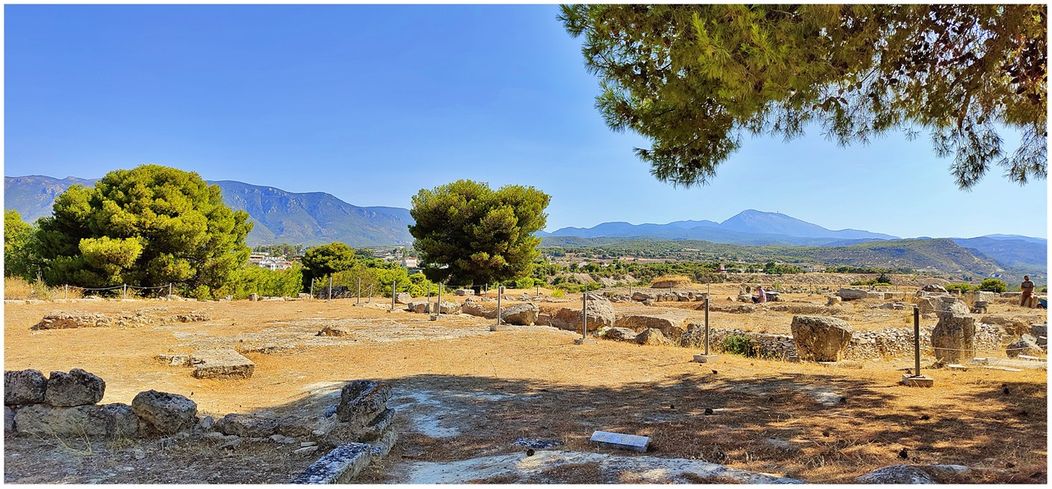

Remains of the Temple of Poseidon.

The Archaic Temple of Poseidon (the first temple), excavated in 1952 by Oscar Broneer, was considered the center of the Isthmian sanctuary. Αs was usual in Greece, faced to the east, and in front was a thirty-meter altar where Poseidon received sacrifices of bulls and sheep or goats. With a similar temple in Corinth, the archaic temple is an early example of monumental architecture on the Greek mainland. Built between 690 and 650 BC, the walls were made of well-out rectangular blocks covered with fine plaster. Large s-shaped terracotta tiles covered the roof (restored in the museum), and on the outside was a peristyle composed of 7 wooden columns at each end and 18 along the sides. Standing against the long walls were piers, probably also of wood.

The temple of Poseidon.

Inside the building, 5 columns supported the ceiling, and another 2 columns stood in the pronaos. A painted frieze may have decorated the interior (fragments in the museum). In the pronaos stood an elaborate marble basin on a stand (περιρραντήριο; restored in the museum), and its round base can be seen in place. The temple also housed shrines to gods related to Poseidon, such as his son, Cyclopes, and the goddess Demeter. A multitude of other named divinities said to have been worshipped within the confines of the temple have links to Demeter, suggesting the Isthmian people's devotion to fertility and harvest. Evidence, including plates, bowls, and animal bones discovered within the ash on the plateau, suggest that animal sacrifices of sheep, cattle, and goats took place at the temple regularly and were often a cause for feasting and celebration.

The temple of Poseidon.

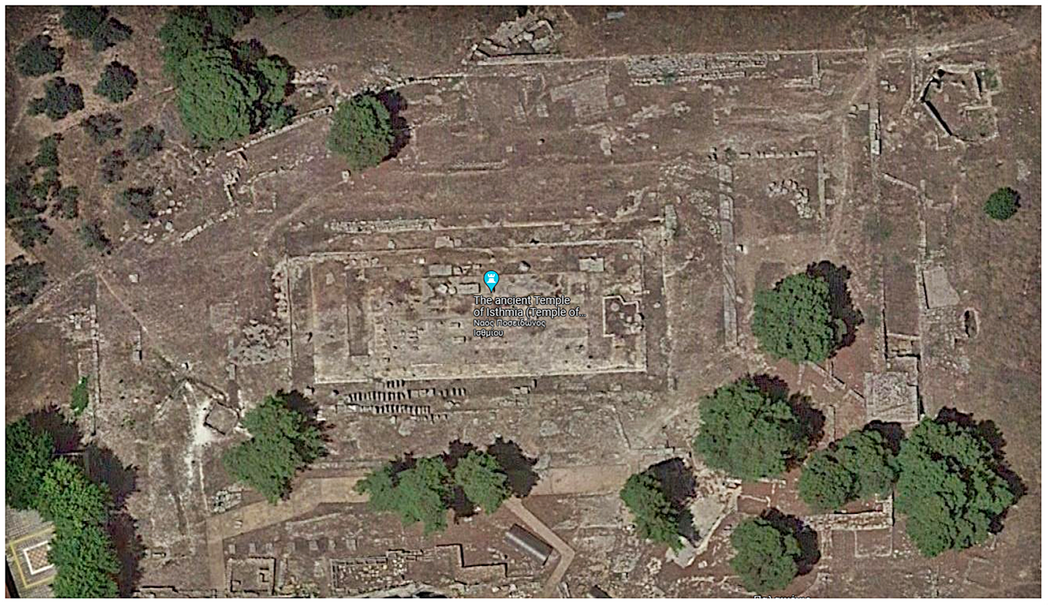

The temple of Poseidon from above. (google maps)

A fire destroyed the building in about 470 BC, and in its place, the Corinthians built a more prominent temple in the Classical Doric order. Trenches for the peristyle and naos were cut out into the rock of the plateau (clearly visible), nearly obliterating traces at the earlier temple. The new building measured approximately 22.90 by 53.50 m., similar to but about one-eighth smaller than the Temple of Zeus at Olympia. The interior preserved the archaic plan of two aisles divided by a single row of columns, unusual for this period. The limestone walls were covered with white stucco, and the roof had marble tiles. A second fire in 390 B.C. destroyed the roof, cornices, and much of the walls. The building was restored similarly to the original (sima (*) in the Museum), but the interior was changed to a canonical three-aisled plan. Nothing remains of the cult statue(s) representing Poseidon and perhaps Amphitrite. After almost two centuries of neglect, the Romans restored the building and added a marble cult group of Poseidon and Amphitrite (torso in the Museum). In the early 5th century A.D., the temple was dismantled to furnish material for the trans-Isthmian fortifications.

(*) In classical architecture, a ‘sima’ is the upturned edge of a roof that acts as a gutter. Sima comes from the Greek ‘simos’, meaning bent upwards.

The temple of Poseidon.

The stadia

The first stadium, built ca. 550 B.C., was oriented northwest-southeast and supported on artificial terracing that changed the contours of the area to what you see today. Its length was 600 Greek feet (= 193 m), but only one end was preserved. This stadium is located inside the archaeological site.

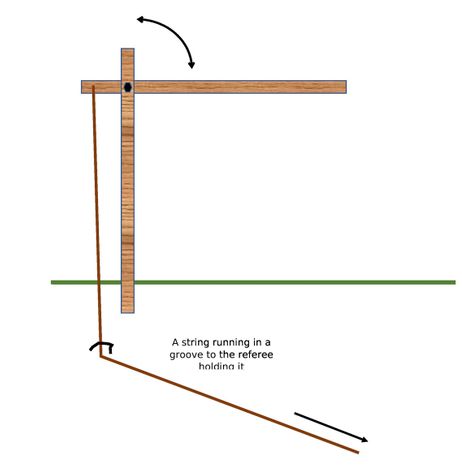

A reconstruction of the "hysplex" of the first stadium.

A ramp connected the stadium with the altar. The first was built of soil, and the latter was enclosed with walls with a gate at the top. Cuttings for the gate are visible in the rock. In the Classical period, the spectator embankment was enlarged, and heavy walls of rectangular blocks (still visible) were built along the outside.

The spectators entered utilizing sloping ramps leading to the top of the embankment. The Classical starting line consisted of a stone sill with one groove for the toes of the runners. Between each runner was a wooden set into a lead bedding (visible). In the 4th century BC, an elaborate and unique starting mechanism was created. Along one side of a triangular pavement, 16 rectangular cuttings held wooden posts but without lead beddings. On one side of each post, a bar was held in place by a rope that ran down to a groove in the pavement and then to a mechanism at the triangle's apex. The ropes holding the bars were released at the start of the race, and the 16 runners began. The arrangement was called a "hysplex" (ὕσπληξ).

Hysplex (Greek: ὕσπληξ) is a starting gate used in ancient Greek horse and foot races. This device was set up at the starting line and consisted of an upright vertical bar with a horizontal gate attached to it held up by a string. Each racer stood behind his hysplex, and the strings were centrally connected behind the runners, held by a referee. At the start of the race, the referee let go of all the strings; consequently, the starting gates fell simultaneously, releasing the runners.

In the 3rd century BC, a new and larger stadium was built in the southeast valley, 250 m. from the temple. It is located outside the limits of the archaeological site, and it is unexcavated except for small tests to show its size, construction, and date. After a period of abandonment from 146 BC to about 50 AD, the stadium was again used for the Roman Isthmian Games.

The theater

The ancient theater of Isthmia is located 100 m northeast of the Temple of Poseidon and east of the baths on the slope of a shallow ravine. To create the appropriate area, one side of the ravine was dug to construct a three-sided cavea for viewers. The orchestra was placed at the base of the cavea, well below ground level. The course of the flume system, which follows the line of the first seats, helps us understand how they were arranged today. This first construction of the theater dates back to the second half of the 5th century BC. It is contemporary with the construction the Classical Temple of Poseidon and the Classical Stadium.

The theater.

The theater from above (Google maps)

About a century later, the theater was reconstructed. The cavea widened and acquired a curved shape. The stage was rearranged, and a proscenium was constructed, whose 11 openings between the support pillars closed with tourniquets. The whole construction was made of wood and could be dismantled between festive periods.

In Roman times, when the Games returned to the sanctuary, the theater’s cavea was expanded even further, creating a 214-degree curve. The stage was reconstructed, possibly for the attendance of emperor Nero in the games of AD 68/69.

The theater orchestra seen from the cavea.

In the 2nd century AD, plans to expand the cavea further until the top of the ravine were concluded, but the works never went beyond laying foundations. The stage building acquired Roman scaenae-frons, but the pulpit was kept high and narrow. Domes covered the two side entrances (parodoi) and the central passage crossing the stage. Two columns of 7.80 m. high with Ionic capitals were standing at the orchestra, possibly as supports of giant statues (12 vertebrae, both capitals, and part of the foundation, were discovered built in the walls of the Byzantine Fortress). Behind the stage was a large courtyard with wooden arcades on both sides. The east and west sides of the court were crossed by roads connecting the theater with some buildings to the north, which have not yet been revealed.

The theater is excavated, but not restored. The visitor, though, has an idea of the size of it.

The Palaemonion

The Isthmian Games, according to legend, began as funeral games for the child hero, Melcertes (Μελικέρτης). When he and his mother, Ino, leaped into the Saronic Gulf (to escape from her husband, king Athamas), both were changed into marine deities: Ino as Leucothea, and Melicertes as Palaemon (Παλαίμων).

A dolphin brought Melicertes' body to the Isthmus and deposited under a pine tree. Here it was found by his uncle Sisyphus, who had it removed to Corinth, and by command of the Nereids instituted the Isthmian Games and sacrifices in his honor. (Alternatively, the Athenians believed their hero Theseus had founded the festival.) The altar and sacred pine tree of Melikertes-Palaemon stood on the shore, where he was worshiped mainly by sailors, as he was their patron.

''The Insane Athamas Killing Learchus, While Ino and Melicertes Jump into the Sea'' by Wilhelm Janson (Holland, Amsterdam), Antonio Tempesta (Italy, Florence, 1555-1630) at Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles

In Roman times, the Palaimonion shrine was built at the southeast corner of Poseidon's temple. Bulls were sacrificed to him in a pit and wholly consumed by fire. Two more pits were opened when the first pit was filled with burned bones, lamps, cups, and bowls. The sacrifices took place at night, and the participants in the rites brought large, round lamps filled with oil.

The first temple dedicated to Palaemon, round with a conical roof, was built in the time of Emperor Hadrian at the east side of Poseidon's shrine, where today, one can see its square concrete foundation. Corinthian coins of this era carried its image.

A few years later, in the Antonine period, the temple was moved south and west and connected with Palaemon's "tomb," by a passage. Coins of the period show the temple and the passage, as well as an olive tree, a bull, and a small raised altar. In the center of the temple was a statue of Palaemon lying on a dolphin's back.

The Palaemonion.

The Cult Caves

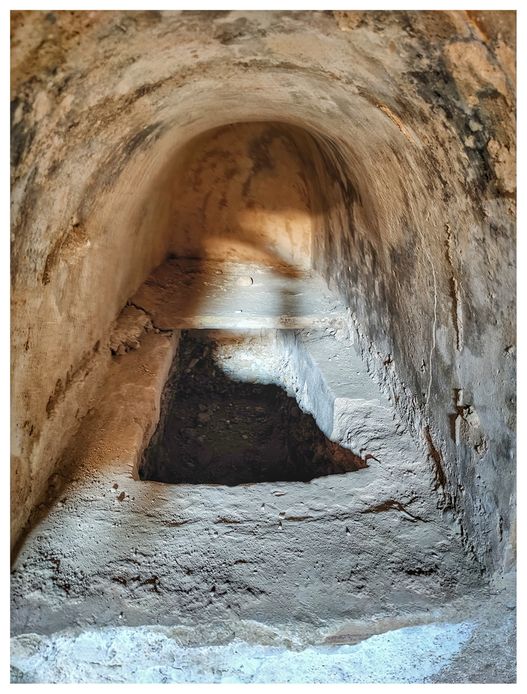

Beneath the rock where the Temple of Poseidon stood was a layer of hard clay cut away at the northeast side of the plateau to create a cave with two chambers. A second, similar cave was made 60 m. away, beneath the rock above the theater. The two caves (Northeast Cave and Theater Cave) followed the same pattern and were made for the same purpose, dining. In two chambers of each cave, couches were cut from the natural clay, 6 in one room and 5 in the other. Perhaps 22 diners could have been accommodated. A short flight of steps from a small courtyard gave access to each room. Food was prepared outside the caves, and at the Theater Cave, two kitchens were found, complete with cooking benches. In one of the kitchens, a set of 17 dishes for preparing the meals had been left in a storage cavity and were undisturbed until excavation in 1959 (vases in Museum).

The Cult Cave located between the theater and the temple of Poseidon.

The caves appear to have been made in the late 5th century BC and continued in use for over a century. The identity of the diners remains a mystery, but they were probably members of a select group who worshipped a deity for whom it was appropriate to feast underground. Above the Northeast Cave was an altar enclosed on three sides and open to the north, but it had no evident access to the cave and may not have been connected with it. No altar was found near the Theater Cave.

The Cult Cave is located between the theater and the temple of Poseidon.

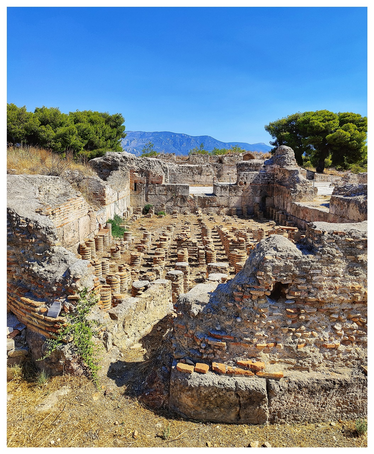

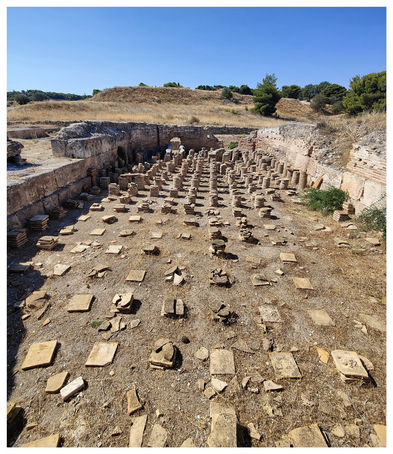

The Roman Baths

The Roman Baths at Isthmia were a luxurious foundation that provided relaxation and delight for visitors and athletes in the Sanctuary for over 250 years. The Baths were constructed about 150-160 AD by a wealthy donor with solid connections to the center of power in Rome. Two portrait heads of Polydeukion (the favorite student of the wealthy Athenian Herodes Atticus) were found in excavations outside the Baths. These suggest that Herodes himself may have built the complex in honor of his young student who had died in his youth.

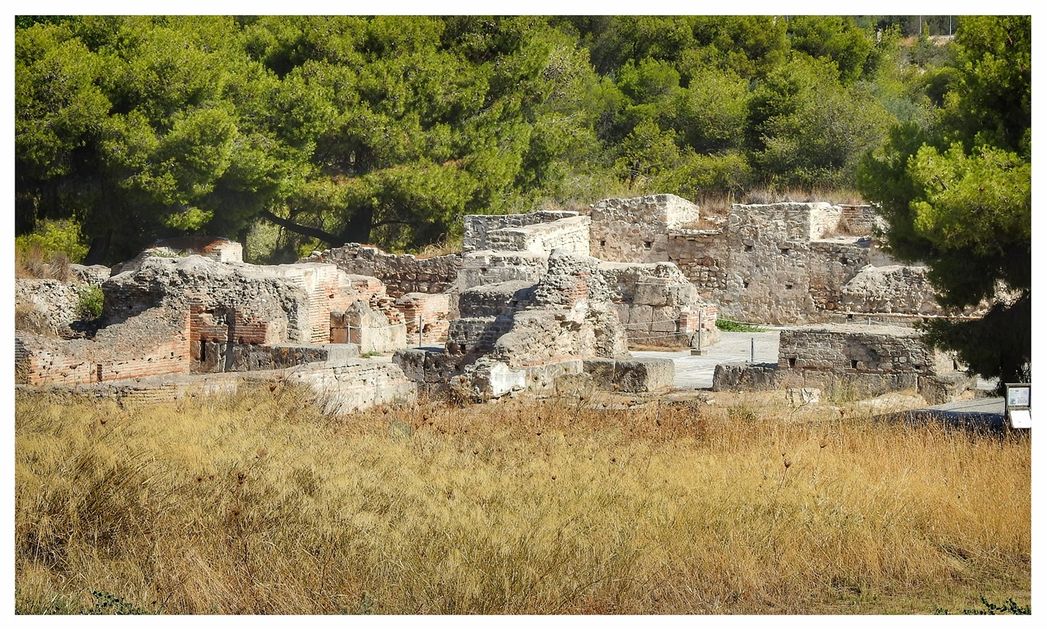

The Roman baths seen from the temple.

The Roman baths.

The fourteen rooms of the Baths were spacious, and massive vaults covered nearly all. The interiors were lit by large glass windows that probably covered the semi-circular spaces at the ends of the vaults. Benches were provided for relaxation, and space was available for socializing, philosophical discussion, and perhaps religious celebrations.

Four rooms were heated by a series of seven individual furnaces, several of which heated large plunge pools. Many details of the heating and drainage systems survive, providing detailed information on the technology available to the builders and those who enjoyed the Roman Baths. The Baths were decorated with sculptures, mosaics, frescoes, and a wide variety of marble brought to Isthmia from all parts of the Roman world; several fountains added to the delight of the senses as cool water splashed down into the large pools.

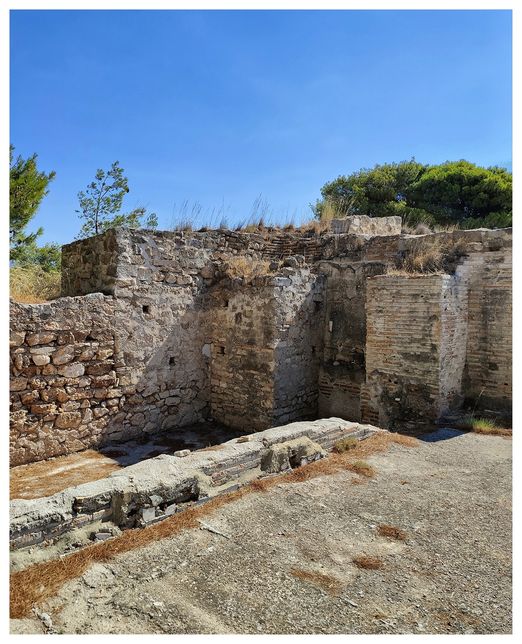

The Roman baths.

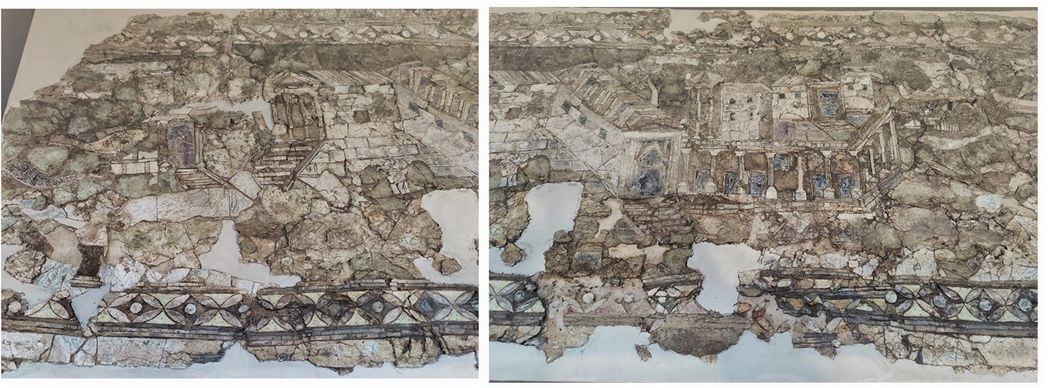

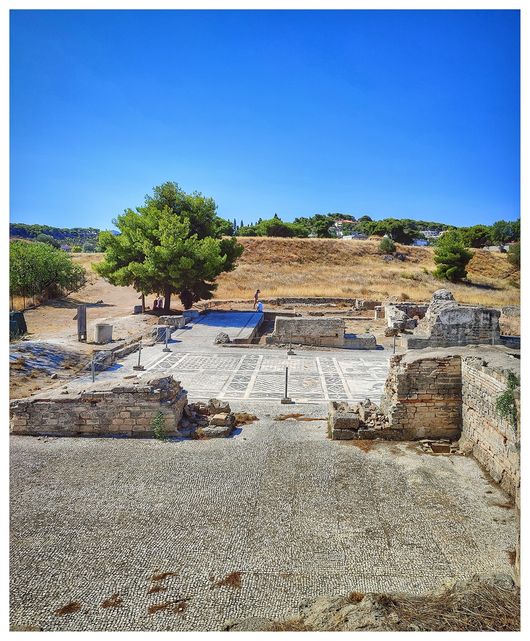

The most impressive part of the decoration was a black and white (monochrome) mosaic 20.2m. long and 7.8m. wide. This mosaic style is most commonly found in Italy, with fine examples at Ostia and Pompeii, but it is very unusual in the Greek East. It is an example of the influence of Roman culture and style in Greece during the Roman Empire. A detailed study of the mosaic techniques, however, suggests that the workers involved in its construction probably were Greeks since they followed more common traditions in Greece.

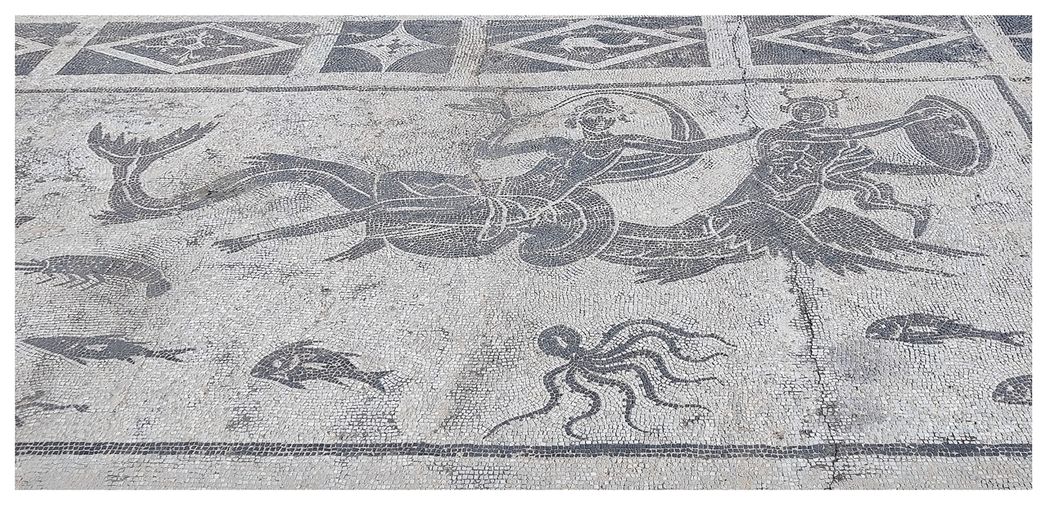

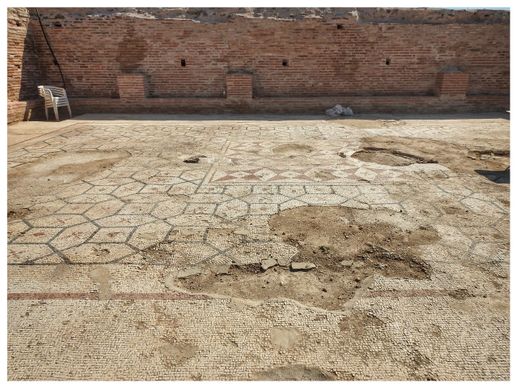

The Isthmia mosaic was discovered in 1976, almost entirely intact, and it is one of the most important finds to come from the excavations at the site. To preserve and protect the mosaic, the whole surface was lifted, cleaned, and replaced in its original position, a task that required the period from 1990 to 2004 to complete. The mosaic comprises three horizontal zones, those on the two sides with square panels of various geometric shapes, while the central zone has two nearly mirror images of a figural scene. This scene depicts a woman, presumably a Nereid or a water spirit riding on the back of a Triton surrounded by lively sea creatures. This scene may have been designed simply for decorative purposes, but it represents a “Marine Thiasos”, a well-known depiction with connections to the worship of Dionysos.

The Roman baths mosaic.

The Roman baths mosaic (detail). This scene depicts a woman, presumably a Nereid or a water spirit riding on the back of a Triton surrounded by lively sea creatures.

The Roman Baths continued to serve visitors to the Sanctuary until their partial destruction, probably by an earthquake in the latter years of the 4 century AD. After that date, the northern Baths walls were incorporated into the fortifications of the Hexamilion, and after a final collapse in the 6 or 7 c. AD, a small Byzantine settlement occupied the Baths site, and its inhabitants engaged in small-scale agricultural activity.

The Roman baths. The under-floor heating system.

The Greek baths

The Roman Baths were constructed on the site of a bathing establishment of the classical period (constructed around 360 BC), showing that this spot was used for bathing for almost a thousand years.

The full extent of the Greek Bath has not yet been exposed, and much of it is still concealed under the walls and floors of the Roman building. Nonetheless, several features associated with the Greek Bath can still be discerned. The classical period bath was used for 500 years until the luxurious Roman building replaced it.

The Greek baths

The most visible feature of the Greek Bath is the floor of the large plunge pool, 80m on a side, with a capacity of over 1200 cubic meters of water. This can be seen in places under roman constructions. The floor of the pool is featureless and is made of waterproof cement. The water came to the pool from the large spring to the southwest, which supplied the area with plentiful water until the 1950s.

Presumably, this Greek Bath was either part of or close to a gymnasium.

As much has been uncovered now, the Classical Bath is the largest found in Greece. Its pool is much larger than the Classical Baths at Delphi and similar but still more extensive than that of Olympia. The athletes undoubtedly used the Bath, but whether it was open to ordinary visitors is unknown.

BEYOND THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITE

The Hexamilion Wall

The Hexamillion (Εξαμίλιον τείχος aka Ιουστινιάνειο τείχος) meaning “six-mile-long” wall, was a defensive fortification built across the Isthmus of Corinth, from the Saronic to the Corinthian Gulf. It was constructed in the early years of the 5th century AD to protect the Peloponnese against barbarian attacks coming from the north.

The Hexamilion Wall on the map (red line).

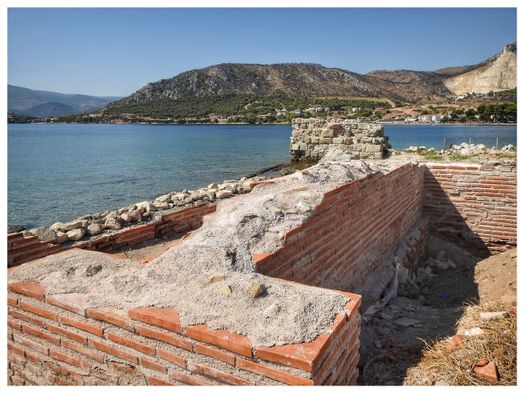

The restored part of the Hexamilion Wall (eastern end).

The Hexamilion was an enormous engineering and military undertaking. It is almost 8 km long, 3 m wide, and 7-8 m high, with more than 100 towers along its line.

The fortification ran along a ridge on the north edge of the Sanctuary of Poseidon, frequently using ancient buildings' foundations to aid its construction. A sizeable Byzantine fortress was built in the vicinity of the Sanctuary, and blocks from many of the buildings in the Sanctuary were removed from the collapsed buildings (including the Temple of Poseidon and the Roman Baths) and used in the fortifications.

The restored part of the Hexamilion Wall (eastern end).

The Hexamilion was rebuilt several times, most notably by the emperors Justinian (527-565) and Manuel II Palaiologos (in 1415). After the Fall of Constantinople (1453), the Venetians attempted to rebuild the walls and use them to defend the Peloponnese against the Ottoman Turks. Still, these ultimately came to nothing as the Venetian state did not have the financial resources to carry out the task.

The Byzantine fortress was part of the Hexamilion Wall.

The fortifications served practical defense needs, and they also figured in myths and stories that represented the hopes and aspirations of the Greek people in the Byzantine period and beyond. A settlement of considerable size grew up within and around the fortifications during the Middle Ages, and this continued to exist apparently until the final abandonment of the Hexamilion in 1715.

Today, traces of the Hexamilion can be seen in many places, and parts of it have been recently renovated and can be visited.

The restored part of the Hexamilion Wall (eastern end).

Kechries Port

Corinth was one of the few Greek cities with two ports, Lechaion in the Corinthian Gulf and Kechries in the Saronic Gulf. The ports were named after the sons, Lechis and Kechrias, of God Poseidon and Pirene, daughter of the river God Acheloos.

Kechries (Cenchreae) was the eastern port of Corinth, located 70 stadiums away from the city, and its peak growth was during the hundred years when Corinth was a Roman Colonia. It had always been the commercial port of Corinth, which was created from a natural bay, and the first technical work is believed to date back to the archaic period. Today, the port consists of traces of adjustments and additional construction works conducted in Roman times. It was horseshoe-shaped with two technical breakwaters that extended far into the sea, creating a 200m opening. Tunnels and harbor facilities surrounded the alcove of the port.

In 53 AD, St. Paul the Apostle set sail from the port of Kechries to Ephesus.

The Kechries port and the Roman cemetary(Google maps).

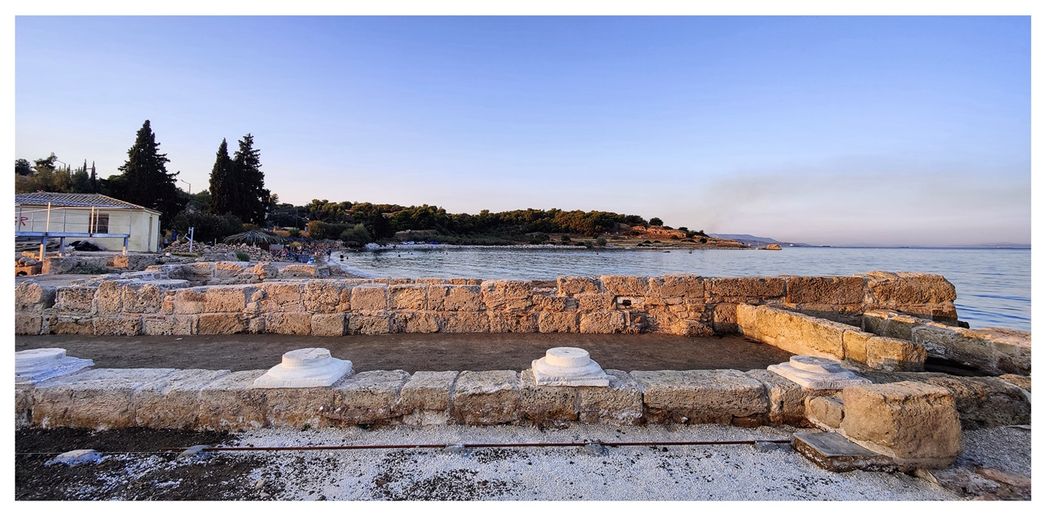

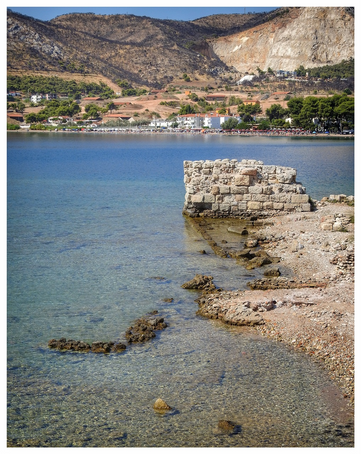

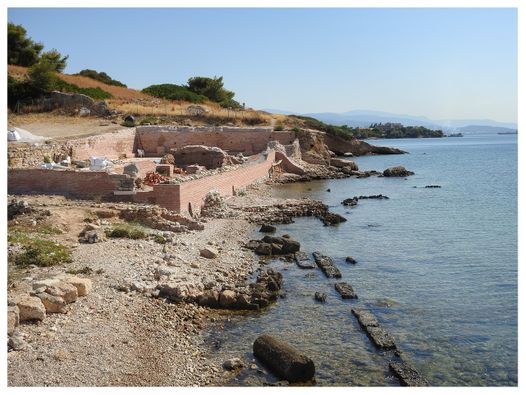

The southern part of the Kechries port. The early christian basilica.

There are two sets of remains of the ancient port. The first set of remains is located on what would have been the southern mole of the crescent-shaped harbor. This port part is fenced (padlocked), and you walk around on the foreshore to get inside. There is a good parking space to leave one's car. Next to it, there is a relatively crowded free beach.

Beyond the basilica, the remains start sinking into the water, many of which seem to be storehouses. A partially submerged apsidal structure can be seen as one more identifiable construction. During the original excavations in the 1960s, this was identified as the Temple of Isis. Subsequent interpretations seemed to dismiss this idea, with some other suppositions being a nymphaeum or perhaps a triclinium or meeting hall for important business meetings. Maybe even just one element of a much larger elite complex. Within this structure, over 100 glass opus sectile panels were found stored in wooden crates, left there, and submerged following an earthquake around 375 AD. The glass panels are now in the Isthmia Archaeological Museum.

Beyond the apsidal structure, only bits and pieces of walls are just above the water's surface. The panels seem to have been shipped from Alexandria, and the interpretation of some of these panels as depicting Nilotic scenes has been cited as evidence that the space could have been related to the Isis cult. One bit of evidence that does favor the Isis theory, though, is the discovery in the immediate area of an inscribed column with the Greek word "Ὀργία"; referring to secret rights or mysteries. This word is interpreted as an epithet of Isis and was also used by Plutarch to describe the mysteries of Isis and Osiris precisely. Like the panels, the column is now at the Isthmia Archaeological Museum.

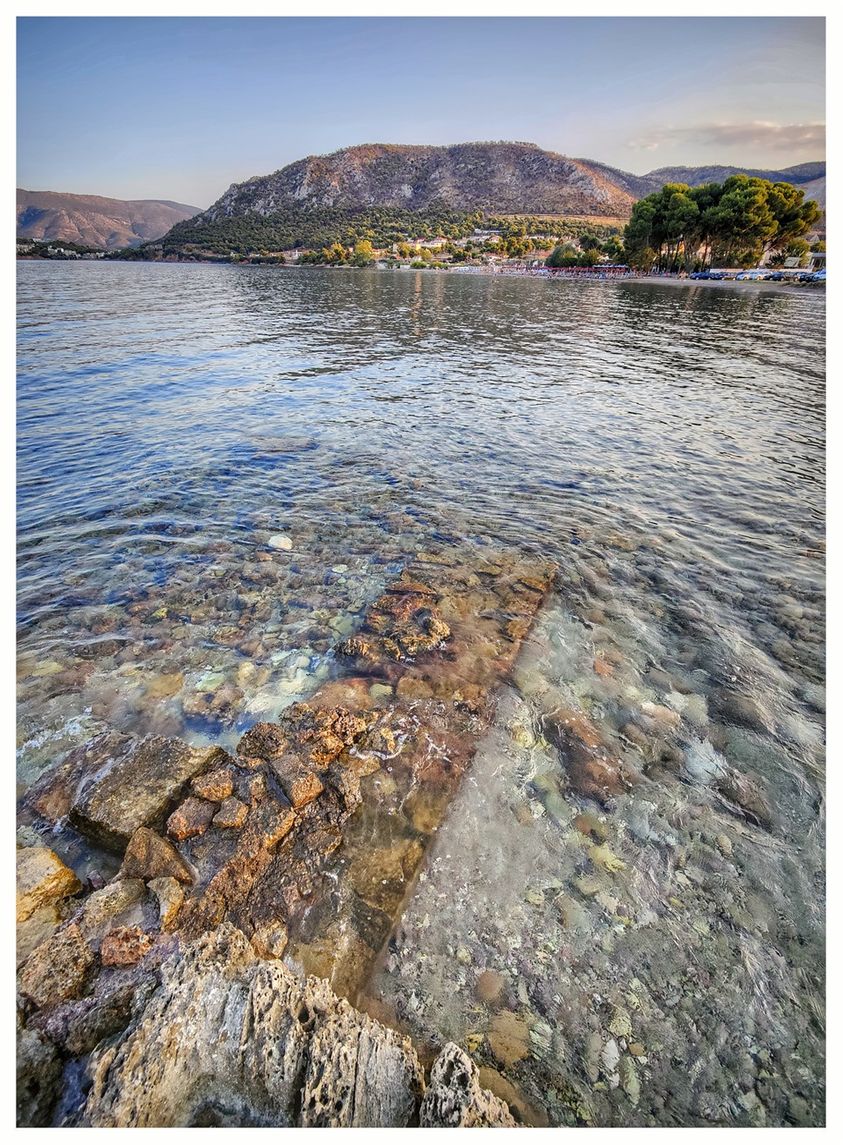

Buildings at the southern part of the Kechries port.

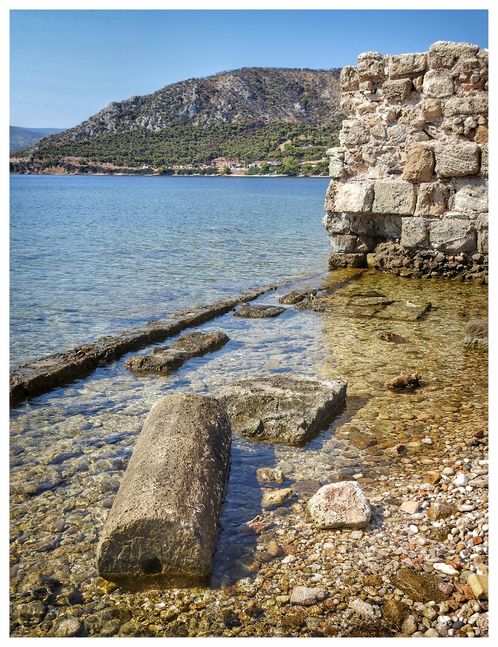

Submerged building remains at the southern part of the port.

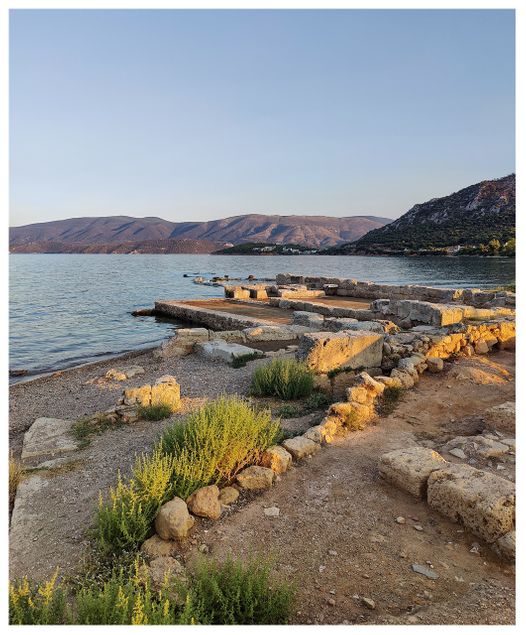

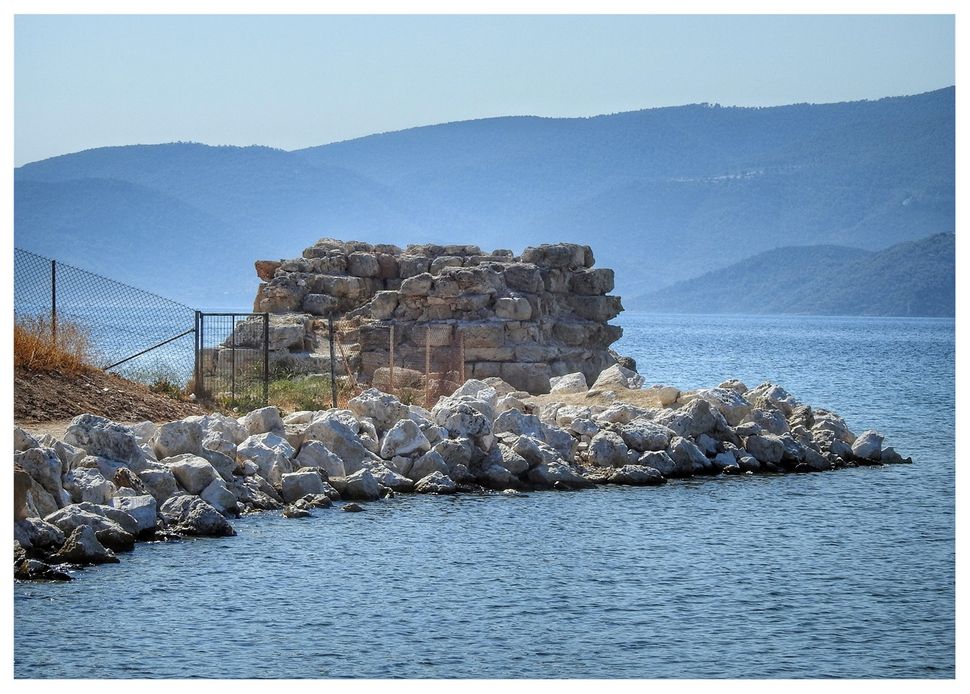

A short walk along the beach northward leads to what would have been the northern mole of the harbor. Alternatively, one may use his car to reach the northern mole. Nothing is left on the actual mole, as there is in the south. A tower is located on the edge of the land before extending out into the area of the north mole. The quadrilateral building (6.5m: 7.5m) made of stone slabs stands at 3.5 m high and is believed to have been a lighthouse or an observatory. Besides being a lighthouse, the "tower of Kechries" was definitely a defensive position and observatory. It was probably built during the last phase of the port, in the 6th century AD.

The northern part of the Kechries port. Remnants of intact marble revetment.

The Tower of the northern part of the Kechries port.

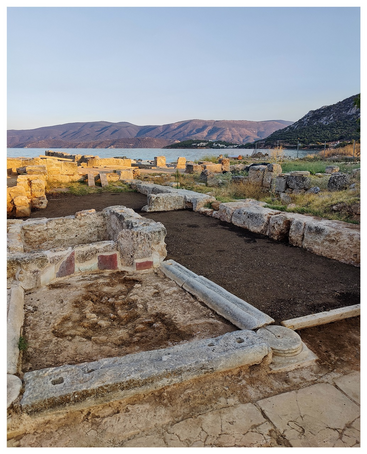

Stretching inward from here is a large complex about 65 meters in length. This structure has long been identified as the Temple of Aphrodite, though this identification seems to derive mainly from Pausanias’ description; he noted that the Isis temple and Aphrodite temple were opposite each other. It does not seem to be any other indication to identify the space as a temple to Aphrodite or, indeed, having any religious function. The building is more likely a wealthy residence. Various building phases between the 1st and 4th centuries AD have been identified.

At the far north end of the complex, there are some intact mosaic pavements that make up the flooring of this area of the residence. This room ends with an intact brick wall preserved up to a significant height (a few meters) where the building abuts the hill that rises from the shore.

There are ongoing works in the building, but the mosaic is uncovered and can be clearly seen.

The "temple of Afrodite" at the northern part of the Kechries port.

Mosaic from the "temple of Afrodite" at the northern part of the Kechries port.

The "temple of Afrodite" at the northern part of the Kechries port.

The big mosaic room of the "temple of Artemis".

The "Kechries Tower".

The Roman Necropolis of Kechries

At the location known as Rahi Koutsogila and extending for about one kilometer north of the port of Kechries, stands a beautiful archeological site, utterly unknown to the general public and unfortunately entirely abandoned.

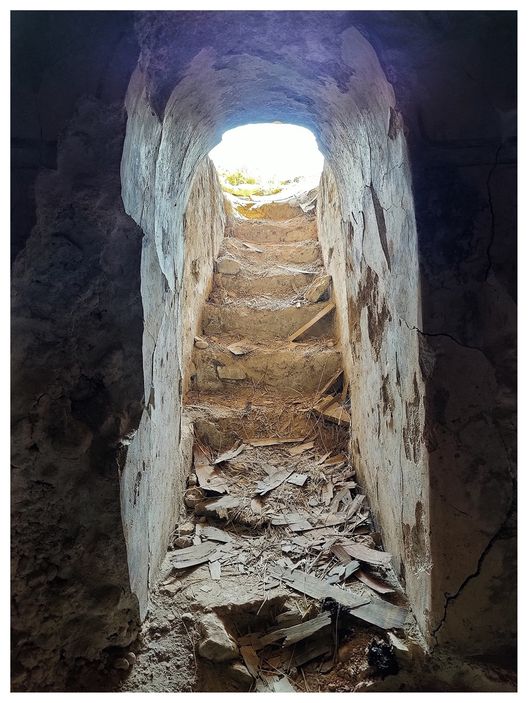

It is easily accessible from the northern arm of the port. A path takes the visitor to a burial place with many tombs. The most important of them have been covered with wooden roofs to be protected from further damage. The roofs are very low, so it is very difficult to enter the tombs. The most impressive of them, where one can see part of the painted decorations (frescos), stands by the coastal cliff, and one can enter, but lots of attention is needed as the entrance is low and slippery.

Systemic excavations, which started in 2002 by the American School of Classical Studies professor Joseph L. Rife, revealed most of this Roman cemetery. Even though poachers have breached the tombs, the systematic investigation revealed essential facts about the burial practices and the community of the port city of Kechries.

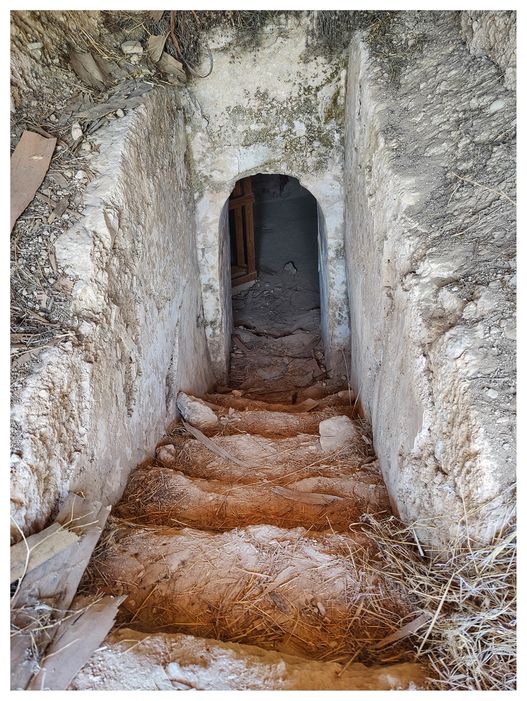

Inside a chamber tomb at the Roman Necropolis of Kechries.

A loculus Inside a chamber tomb at the Roman Necropolis of Kechries.

Loculi and niches inside a tomb at the Roman Necropolis of Kechries.

The cemetery began to be used in the middle and towards the end of the 1st century AD. The chambered tombs were used for burials until the 5th-6th century AD and maybe later. Interestingly, it is the only roman burial site we know that continued to be used by Christians. The chambered tombs are the most impressive burial structures in Kechries. They were usually covered by buildings bearing epitaphs with the engraved name of the tomb owner. They were used as family tombs.

The burial chambers were accessible by descending stairs and had burial sites on the walls. These places were once elongated for burials (loculi) or had the form of a small niche for the placement of urns in cases of cremation of the dead. The mourners performed funeral rites inside the tombs and used stone structures such as desks and altars. The walls of the tombs were covered with mortar colorless or painted with geometrical forms, flowering plants, garlands, animals (herons, swans, dolphins) and mythical creatures. The vivid murals highlight the creative talent of local artists through their symmetrical arrangement in space, the combination of bold outlines with delicate silhouettes, and the adoption of ordinary Hellenistic and Roman traditional wall decorations.

The entrance to a chamber tomb at the Roman Necropolis of Kechries.

Tombs at the Roman Necropolis of Kechries.

The entrance to a chamber tomb at the Roman Necropolis of Kechries.

Covered chamber tombs at the Roman Necropolis of Kechries.

The dead were endowed with many offerings: coins in the mouth or above the chest, gold rings and earrings, bone forks, clay figurines, marble statuettes, amphorae and household utensils, cups, flasks, shovels, tables, etc.

The scientific analysis of the bones from various chamber tombs proved that about 50-100 people of all ages, men and women, were buried in each of them.

The exceptional diligence found in the tombs' construction, decoration, and use leads to the conclusion that they belonged to upper-class people of the local community. In addition, the relative uniformity that prevails in the design of the tombs in Kechries shows the will of their owners to identify themselves as members of a prominent social class.

The Roman Necropolis of Kechries.

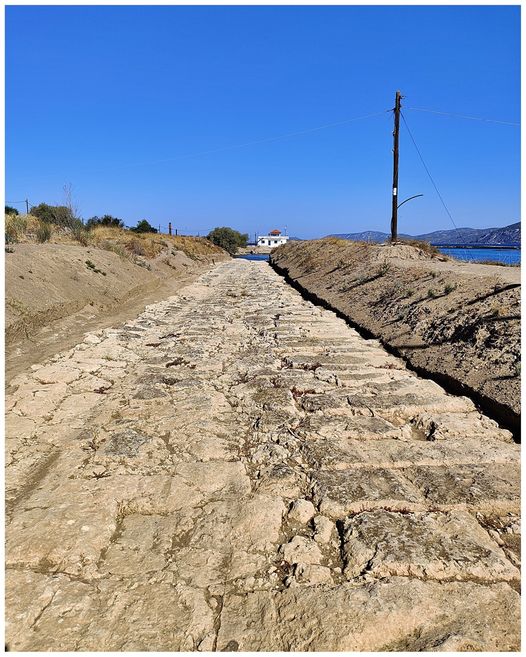

The Diolkos

The Diolkos (Δίολκος) was a paved trackway in Ancient Greece which enabled boats to be moved overland across the Isthmus of Corinth. The shortcut allowed ancient vessels to avoid the long and dangerous circumnavigation of the Peloponnese peninsula. The phrase "as fast as a Corinthian", penned by the comic playwright Aristophanes, indicates that the trackway was common knowledge and had acquired a reputation for swiftness.

The primary function of the Diolkos was the transfer of goods, although, in times of war, it also became a preferred means of speeding up naval campaigns. The 8 km long roadway was a rudimentary form of railway operated from c. 600 BC until the middle of the 1st century AD. The Diolkos combined the two principles of the railway and the overland transport of ships on a scale that remained unique in antiquity.

Part of the restored Diolkos.

The restored western part of diolkos.

The chief engineer of the Corinth Canal, Béla Gerster, conducted extensive research on the topography of the Isthmus but did not discover the Diolkos. Remains of the ship trackway were probably first identified by the German archaeologist Habbo Gerhard Lolling in the 1883. In 1913, James George Frazer reported in his commentary on Pausanias traces of an ancient trackway across the Isthmus, while Harold North Fowler discovered parts of the western quay in 1932.

Systematic excavations were finally undertaken by the Greek archaeologist Nikolaos Verdelis between 1956 and 1962, and these uncovered a nearly continuous stretch of 800 m and traced about 1,100 m in all. Even though Verdelis' excavation reports continue to provide the basis for modern interpretations, his premature death prevented complete publication, leaving many questions concerning the exact nature of the structure. Additional investigations in situ, meant to complement Verdelis' work, were later published by Georges Raepsaet and Walter Werner.

Today, erosion caused by ship movements on the nearby Canal has left considerable portions of the Diolkos in a poor state, particularly at its excavated western end. Critics who blame the Greek Ministry of Culture for continued inactivity have launched a petition to save and restore the registered archaeological site.