(Part I)

PALERMO

Introduction & a Tour Around Quatro Canti

January 2020

Note: In my article about Catania, you will find much information about Sicily; its history, culture, colors, smells, food, etc.

Orientation

Palermo (Panormos in Ancient Greek) city is the capital and the most populous city on the island of Sicily. Sicily is the largest island of Italy, seemingly kicked into the Mediterranean Sea by the boot-shaped country.

Palermo lies on Sicily’s northwestern coast at the Bay of Palermo (Tyrrhenian Sea), facing east. Inland the city is enclosed by a fertile plain known as the Conca d’Oro (Golden Shell), planted with citrus groves and backed by mountains. Mount Pellegrino rises to a height of 606 m north of the city.

Palermo is a bit more chaotic and ‘rough and ready’ than Catania, but that doesn’t make it any less worth visiting. On the contrary, boasting fine medieval sites and fine churches (12 UNESCO sites across the Palermo province), it’s certainly one of the cities that must be visited. While Catania is more “noble,” Palermo is more “Sicilian” and infamous as the mafia's capital. There are no chances for a tourist to get involved with organized crime, but the idea certainly gives the city those “Vivere pericolosamente” mysterious vibes. The only danger one may face in Palermo is to get some extra kilos trying local food such as arancine, panelle, pizza, pasta, and cannoli.

The easiest way to get there is by plane. Palermo Falcone Borcellino Airport (PMO) is the biggest in Sicily. Alternatively, fly into Catania-Fontanarossa Airport (CTA) on the other side of the island, and get the train or bus across. If you want to explore the whole of the island (providing you have at least two weeks to spare), you can land on one of the airports and depart from the other.

From Falcone Borcellino Airport, it is easy to arrive in the city center by Shuttle bus, train (Trinacria Express runs between the airport and Stazione Centrale every hour), or taxi (around €35). The journey takes 35-45 minutes, depending on the traffic.

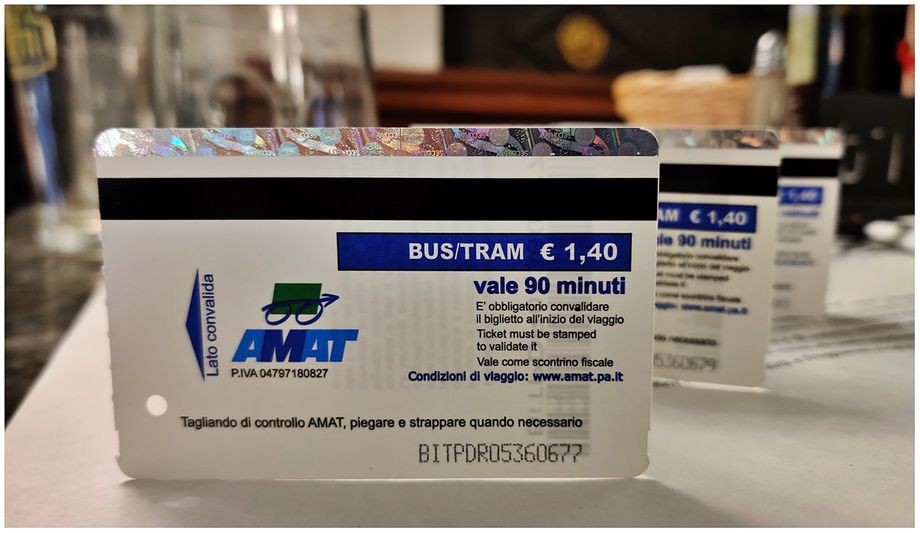

I always recommend staying at the center of the city and explore it on foot. Palermo is a completely walkable city, but one can always rent a bike or use public transport: the AMAT bus and tram network. You can pick up 90-minute tickets for €1.40 at AMAT kiosks and tabaccherie (tobacconists), or you can buy tickets on the bus, valid only for that bus ride, for €1.80. Don’t forget to validate your ticket on the bus/tram, or you could get a fine!

Public transport (valid for 90-minute) tickets cost €1.40.

A brief History

Phoenician traders founded Palermo in the 8th century BC. They named it Zyz (which in their language meant flower). Zyz would be significant due to its location, which would become a popular destination for the Greeks. At one time, the Greeks would populate a large part of eastern Sicily, but they would never officially conquer it. The Greeks would also rename Zyz to Panormos (“all-port”). While this was namely due to the natural harbor that was built by the crossing of the two rivers, this name would catch on quickly as Greek influence began to set in.

The Phoenicians would remain in control until the First Punic War (between 264 and 241 B.C.) Palermo would actually be at the heart of the dispute between the Romans and the Phoenicians from Carthage. Romans would eventually win out, and their rule in Sicily would last from 258 BC, when Palermo was conquered, until 491 A.D. During this time of barbarians, the city would be captured by Ostrogoths. The city decayed under Roman rule but prospered after AD 535 when the Byzantine general Belisarius recovered it from the Ostrogoths.

The Arabs conquered Palermo in 831, and it flourished as a center of rich trade with North Africa. Arabs made Palermo a capital in their Sicilian Emirate. Under Arab control, the city was being called Balarm. From 827 to 1061, this Arab control would inspire social, economic, and cultural advancements that still shine in traditional Sicilian practices today. A noteworthy concept that has been very dear to Sicilians is their close relationships with family. Balarm's population reached more than 250,000 residents. At this time, both Rome and Milan were only inhabited by around 30,000 people! The Arab dominion was one of Sicily’s longest-ruling eras, and it left the biggest impact on current Sicily. Over the span of around 200 years, Palermo has been forever changed through the customs, traditions, and culture present during this time period.

Sicilian Emirate emblem.

The Arabs also had a large part in inspiring the cuisine within Sicily. Spices, sugars, and various aromas were staples of Arabic foods and are still present in traditional Sicilian dishes.

After 5 long years of siege, the Arabs would lose control of Palermo to the Normans in 1072. Palermo was thus quite prosperous when it fell to the Norman adventurers Roger I and Robert Guiscard. The ensuing era of Norman rule (1072–1194) was Palermo’s golden age, particularly after founding Sicily's Norman Kingdom in 1130 by Roger II (Ruggero II). Palermo became the capital of this kingdom, in which Greeks, Arabs, Jews, and Normans worked together with singular harmony to create a cosmopolitan culture of remarkable vitality.

Norman rule in Sicily was replaced in 1194 by that of the German Hohenstaufen dynasty. The Hohenstaufen Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II shifted the center of imperial politics to southern Italy and Sicily. The cultural brilliance of his court at Palermo was renowned throughout western Europe. The city declined under succeeding Hohenstaufen rulers.

Norman Kingdom of Sicily emblem.

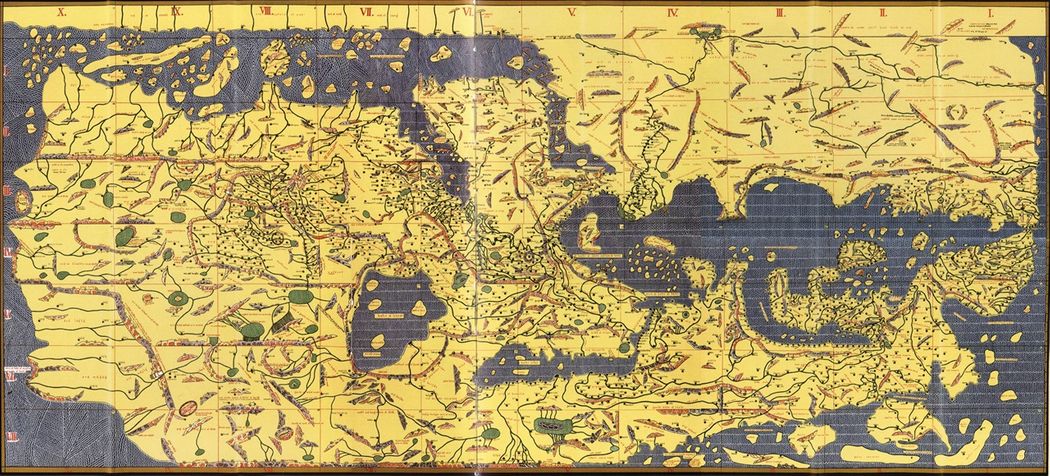

The Tabula Rogeriana, an ancient world map drawn by Muhammad al-Idrisi for Roger II of Sicily in 1154. The north is at the bottom, and so the map appears "upside down" compared to modern cartographic conventions.

The French Charles of Anjou conquered it in 1266, but Angevin's oppression ended in 1282 by a popular uprising called the Sicilian Vespers. Palermo then came under Aragonese rule. After 1412, Sicily's crown was united with that of Aragon and subsequently with that of Spain in 1494. Palermo declined during this long period of Spanish rule. 1713 would see the end of Spanish rule when the Bourbons arrived, and the Peace of Utrecht was agreed upon.

The Sicilian Vespers (1865) by Michele Rapisardi.

The Landing of Garibaldi (Expedition of the Thousand) in 1860 would cycle the end of Bourbon rule over Palermo and unify Sicily to Italy's Kingdom (1861).

In the early parts of the 20th century, Palermo would flourish in many ways. The economy and cultural growth were unlike anything the city had seen for centuries, especially in Art Nouveau's style.

The city was severely bombed in July 1943, when Allied troops took it. Parts of old Palermo, where buildings were destroyed during World War II, remained unrestored into the 1990s. One of the reasons is the strange way the local government and mafia's interests are interlaced, creating a chaotic situation. Even though the city is so culturally significant, you can still feel the weight and strain that the Sicilian Mafia has on Sicily's social and even economic state.

Food

An article about Palermo and Sicily would be void without talking about food, omnipresent on this blessed island. You can find more on Sicilian cuisine in my articles about Catania.

I believe no person on this planet does not enjoy the four Italian staple foods: pasta, pizza, gelato, and (espresso) coffee. Italy taught people how to enjoy food, and this joy, of course, is present in every street, alley, and piazza in Palermo.

Only imagination can stop the variety of pasta dishes in Sicily.

As this is not good enough, Palermo offers a cornucopia of Sicilian dishes. Sicilian cuisine shows traces of all cultures on Sicily's island over the last two millennia. Although its cuisine has a lot in common with Italian cuisine, Sicilian food also has Greek, Spanish, French, and Arab influences, making Sicilian cuisine a veritable melting pot of flavor. Typical ingredients of Sicilian dishes are pasta, tomato, aubergines, pistachio, olive oil, fresh fish & seafood, ricotta cheese, ragusano cheese, pecorino Siciliano cheese, almonds, horse meat, wine, citrus fruits, raisins and saffron, basil, garlic (“aglio rosso di Nubia” is a local garlic variety), pine nuts, etc.

Pistachio is extremely popular in Sicily and is used in confectionery and cooking. Italian hot and thick chocolate (budino) sprinkled with pistachio (left), and white chocolate-pistachio cake at 'Antico Caffe Spinnato' (right).

In Palermo, one can taste all kinds of Italian and Sicilian food and some very local delicacies eaten only here. My list of Palermitan dishes that follows is certainly not complete but gives a good picture of what the visitor would expect from his holidays here.

Espresso is an Italian staple food. Enjoy it at any time of the day.

Torta Setteveli

Torta Setteveli is truly a work of culinary art. Named after Salome's dance to make Herod crazy with lust, torta setteveli (cake of the seven veils) unsurprisingly achieves more or less the same results. This traditional Sicilian birthday cake consists of an alternating combination of chocolate and hazelnut layers. From bottom to top: chocolate sponge, praline crunch, hazelnut Bavarian cream, chocolate sponge, hazelnut Bavarian cream, chocolate mousse, and finally, a layer of chocolate glaze on top.

Torta Setteveli at Pasticceria Capello in Palermo.

There are many stories about who actually created the cake. Some give credit to Capello of Pasticceria Capello in Palermo, others to Luca Mannori of Prato, whose Torta Setteveli helped him win the 1997 Pastry World Cup in Lyon, France. You can find the cake throughout Sicily, but it is in every pasticceria in Palermo. The Palermitani see it as the ultimate dessert to enjoy on special occasions, especially for birthdays. It definitely lives up to its billing. Each layer is creamy and rich but also as light as one of the veils Salome’s dance.

Pasticceria Capello in Palermo.

Today, besides the traditional taste, there are varieties, with different colored layers, like green-pistachio. I had delicious Torta Setteveli; where else? At Pasticceria Cappello (Via Colonna Rotta, 68) of course. You can either take away your cakes but also enjoy them with an aromatic espresso at one of the two only tables outside the shop.

PIstachio Torta Setteveli at Pasticceria Capello in Palermo.

Zeppola

A zeppola (also known as frittelle) is a pastry consisting of a deep-fried dough ball of varying size but typically about 10 cm. This doughnut or fritter is usually topped with powdered sugar and maybe filled with custard, jelly, cannoli-style pastry cream, or a butter-and-honey mixture. The consistency ranges from light and puffy to bread/pasta-like.

Zeppola was eaten to celebrate Saint Joseph's Day, but of course, today can be found and enjoyed every day of the year.

Zeppola.

Cannoli, the Sicilians’ pride and joy

Cannoli come from the Palermo and Messina areas and were historically prepared as a treat during Carnevale season, possibly as a fertility symbol. The dessert eventually became a year-round staple in Sicily. Cannoli are very popular in Italian American cuisine.

Enjoying a pistachio cannolo at 'Cannoli & Co' in Via Maqueda.

Cannoli consist of tube-shaped shells of fried pastry dough, filled with a sweet, creamy filling usually containing ricotta. They range in size from "cannulicchi," no bigger than a finger, to the fist-sized proportions typically found south of Palermo, in Piana degli Albanesi. In Italy, they are commonly known as "cannoli siciliani."

Canolli.

Cannolo is the singular word, meaning "little tube," but in English, cannoli is usually used as a singular and a plural. Some similar desserts in Middle Eastern tradition include Zainab's fingers, which are filled with nuts, and qanawāt, deep-fried dough tubes filled with various sweets, a popular pastry across the ancient Islamic world. The dish and the name may originate from the Muslim Emirate of Sicily.

Cannoli come in any size!

Panelle

These iconic street food items are essentially fritters that are made from chickpea flour. Born as a food for poor people, Panelle (paneddi in Sicilian) conquered the palate of all the social classes: from the poorest to the noblest! You will find that they are often served as a sandwich in bread rolls covered with sesame seeds, called Mafalda or Muffola. When served like this, it is known as Panino con le Panelle or better in Sicilian “U pani chi Panelli (Bread with Panelle).”

Freshly fried Panelle at 'Antica Focacceria San Francesco'.

Over the centuries, the Pannellaro that is the informal name of the Panelle’s vendor, is a mythical figure able to gather different people: from the poorest to the richest, passing from nobles, villagers, working-class people, intellectuals, thieves, artists, and crooks. All the classes are equal around the big cauldron filled with hot oil where the Panellaro fries the Panelle!

Street vendor selling milza, panelle and crocche at Ballaro Market.

Chickpeas flour is known and used in Italian cuisine since Roman Empire times. Likely, the introduction of chickpeas is due to the Greek and Middle East influences. The Ancient Romans used to prepare a mixture of hot water and chickpeas flour: not really appetizing! In Sicily, the first recipe of chickpeas fritters comes with the occupation of the Arabs between the IX and the XI Century. The new invaders introduced this fried delicacy, inspired by a Carthaginian recipe. In a few years, Panelle has become food for the poor people, thanks to the inexpensive ingredients. The Panelle were enriched with parsley and lemon juice, traditional ingredients for seafood, and sold as a fish substitute: the people used to call the fritters Panella fish! As the years passed, the Panelle has been appreciated by rich people, intellectuals, and nobles. Several famous Sicilian public figures: for instance, the writers Leonardo Sciascia and Luigi Pirandello, or the Painter Renato Guttuso, had a particular taste for Panelle, spread the popularity of these fritters.

Sfincione

Panino con le Panelle or “U pani chi Panelli" (Bread with Panelle).

Traditional Sicilian pizza is often thick-crusted, rectangular, and less often round and similar to Neapolitan pizza. It is often topped with onions, anchovies, tomatoes, potato, olives, sausage, herbs, and strong-taste cheese such as caciocavallo and toma. Other versions do not include cheese.

The Sicilian methods of making pizza are linked to local culture and country traditions, so there are differences in preparing pizza even among the Sicilian regions.

Sicilian pizza is often thick-crusted and rectangular.

The Sfincione (sfinciuni in Sicilian) is originated in the province of Palermo and is one of the most popular and traditional Sicilian pizzas. This thick flatbread seasoned with a tasty tomato sauce, preserved anchovies, and Sicilian cheese is a street food delicacy easy to find in the Palermitan markets: a must-to-try with a very ancient history.

Note: In the United States, "Sicilian pizza" is used to describe a typically square variety of cheese pizza with dough over an inch thick. It is derived from the sfinciuni and was introduced in the United States by the first Sicilian immigrants.

Sfincione (sfinciuni in Sicilian) is one of the most popular and traditional Sicilian pizzas, and the most popular street food.

The Sfincione is one of the must-to-try Sicilian street foods. This recipe was initially prepared during the Christmas festivities, but nowadays is baked and served all year long. The origin of the name gives us a clue of the antiquity of this recipe: it seems to result from the Latin Spongia and Greek Spongos, that means both of them “Sponge”. The Sfincione is also named Origanata, thanks to the plenty of oregano used to make the sauce. Even if the Sfincione is easy to find in all the Palermitan area, the most traditional area where to find this delicious pizza is the Alberghiera district in Palermo, and particularly, Porta Sant’anna. The Sfincione‘s vendors are called Sfinciunari in the Palermitan dialect: they drive around the open air markets and stops on the crossing streets selling Sfincione on board particular three-wheel motorcycles called Ape Piaggio.

Enjoying sfincione at 'Mercato del Capo' (Via Porta Carini).

Along with the tomato sauce, the cheese is the protagonist of the Sfincione recipe. Basically, the cheeses used to prepare the Sfincione are two. The first one is a semi-soft cheese, traditionally Primo Sale or young Caciocavallo. This cheese is diced and placed on the flattened dough before spreading the tomato sauce. In case these cheeses are not available, a decent option is a semi-soft goat cheddar. The second cheese is the Ragusano (alternatively replaced with Pecorino), grated over the other toppings. The amount of Ragusano is personal: some chefs use an abundant quantity, some others a tiny portion.

In Bagheria, a little town near Palermo, it is traditional to make white Sfincione with ricotta cheese instead of tomato sauce.

Delicious 'Sfincione all'metro'.

Stigghiola

Stigghiola is a great afternoon snack on this “best of” list. These are skewered innards (usually of lamb) that are seasoned with parsley and then grilled. After they have cooked, they are cut into pieces and seasoned further with lemon and salt. This is a timeless classic of Sicilian cuisine, pairing the melted fat and the roasted meat's crunch.

Stigghiola.

Pezzi Di Rosticceria

Pezzi Di Rosticceria are brioche doughs that are baked or fried after being stuffed with various toppings. One of the first solid foods Sicilian children eat will be Pezzi de Rosticceria, and this food and its hauntingly delightful flavors combined with childhood memories will accompany a Sicilian all the rest of his or her life. As a child, you eat them for breakfast. As a teenager, you eat them for a nighttime snack (they’re sold twenty-four hours a day). This helps to absorb and disguise all the many drinks you’ve illicitly had before you come home, and as an adult, it makes for a great dish to eat quickly when you have to get back to work.

Pezzi Di Rosticceria.

There are sold in many cafeterias around Palermo. It’s almost laughable to watch the locals standing before a counter displaying all varieties at breakfast time. They begin by sharing one or two pieces of brioche, pretending not to want to overeat, and then finish their breakfast by sharing at least three or more half-pieces!

Below you will find the most traditional (and famous) pezzi di rosticceria in all of Sicily. Calzone (baked brioche with ham and mozzarella); Rollo con Wurstel (baked brioche with wurst); Rollo con Prosciutto e Mozzarella (baked brioche with ham, béchamel, and mozzarella); Pizzotto (baked brioche with mozzarella and ham with tomato sauce on the top); Spiedino (fried brioche with minced meat, tomato sauce and peas); Ravazzata (baked brioche with minced meat, pepper, peas and tomato sauce); Pizzetta (Small pizza with soft and thick dough, usually consists of tomato sauce and mozzarella cheese.

Pezzi Di Rosticceria can be enjoyed best with a cold beer or a glass of local limonata.

Pane con la Milza

Pane con le milza (aka 'pani ca meusa' in Sicilian) translates to a sandwich stuffed with the veal's spleen. It looks a lot like a good old American hamburger. I didn’t say ‘tastes like’; just ‘looks like.' I can imagine your face right now as you read “spleen of veal.” Yes, among the other mysterious ingredients you won’t be able to identify in your sandwich, a major ingredient is the spleen of veal, along with lung and trachea. Now, we all have a spleen which some claim in a vastedda (the traditional Sicilian bread used to prepare the Pani câ meusa) tastes something like chicken liver. Others have widely varying opinions. It’s something you have to try once. I mean, it won’t kill you. Many say the flavor is too strong, but this sandwich is really very tasty. When the lung, trachea, and spleen of veal are cooked together over low heat in copper pans with diet-busting lard, you’ll become a believer. Unlike the panelle, pane con la milza can’t really be eaten without the bread. You can add lemon squeezed over the sandwich to ease the punishment your stomach may encounter.

The 'pani ca meusa' (pane con la milza) comes in two versions. Schietta means single and only contains the above-mentioned ingredients. The Maritata (married) adds flakes of ricotta cheese on top.

One of the more famous places to eat pane con la milza is Porta Carbone. Cars and trucks normally form a complete traffic jam in front of the shop while they vie with the others to get their hands on a spleen sandwich before setting out for their day’s work. This ritual consists of having a pane con la milza before getting behind the wheel to start their journey. When I consider the time, from about seven to nine every morning, I can’t really speak about breakfast but the courage it takes to get up there and get a sandwich to down before heading out to work takes some real manly courage.

Milza cooked in 'Antica Focacceria San Francesco'.

Caponata

Arguably Sicily’s most famous culinary export, caponata, is now seen on menus across Europe and elsewhere. The recipe can change from household to household, but it must always contain aubergines, pine nuts, raisins, and plenty of vinegar. Served at room temperature, usually as an antipasto, the fried aubergine is turned into a stew with celery, onion, and tomatoes before being flavored with capers and olives, pine nuts, and raisins. The sweetened vinegar finishes it off with a lovely tang.

Caponata in "Il Covo del Pirata' in Cefalu.

Caponata.

Caponata at 'Antica Focacceria San Francesco'.

Buccellato

Buccellato is a Sicilian ring-shaped cake, which contains dry figs and nuts. It is traditionally associated with Christmas in Sicily. It is not to be confused with the distinct but similar traditional Lucchese cake of the same name, the Buccellato (di Lucca), although both are ring-shaped sweetbreads that contain candied fruit peels. Sicilian buccellato is not always big ring-shaped but also comes in a small elongated form.

Small buccelatto.

Christmas time. Buccelato at the windows of "Antica Caffe Spinnato".

Frutta martorana

The Arab candy makers heavily influenced marzipan in Sicily in the 9th century, and Sicilian marzipan has preserved more of that influence than almost any other place in Europe. Marzipan fruits (frutta di martorana) may have been invented at the Convent of Eloise Martorana in the 14th century (located once next to Santa Maria dell'Ammiraglio on Piazza Bellini in central Palermo).

Frutta martorana.

Frutta di Martorana making has been evolved into a real art of sculpture and painting: the good ones have a unique resemblance to real fruit. The shop windows in Palermo are full of big trays or baskets full of marzipan fruit of all kinds. The outstanding ones, both in taste and realistic appearance, are costly.

Christmas window with Frutta Martorana and 'prickly pear-Χmas tree' marzipan.

Granita

Granita, a popular flavored sherbet, is believed to hail from Catania, even though there is no evident proof that it hails from any particular Sicilian city. It is a semi-frozen dessert of sugar, water, and flavorings originally from the island. The most common flavorings are almond, lemon, pistachio, coffee, chocolate. Related to sorbet and Italian ice, it has a coarser, more crystalline texture in Sicily.

Gelato in brioche sandwich.

Arancina

Granita con brioche.

In Palermo, granita is usually served with warm brioche (granita con brioche) or brioscina. The brioche is served on a separate plate, but famous is the awkward idea of a sliced brioche filled with the ice-cream! Granita con brioche is especially welcome in the baking heat of summer, and you'll often see cafés full of people enjoying this excellent combination as breakfast before getting ready for the day ahead. Of course, it is not only granita that is served with brioche. None prevents you from devouring your old good gelato in this way, too.

The Queen of Palermo’s street food can be found in most of the city's bars and restaurants, but few of them cook it as the Sacred Grandmother Rules dictate. The arancina, whose name is due to its appearance that reminds an orange (arancia, in Italian), is one of the many Arab legacies of Sicilian cuisine. It is a rice ball infused with saffron flavor, traditionally stuffed with ragù sauce (tomato, minced meat, peas, onion) and seasoned cheese, or with mozzarella cheese, ham and butter, then covered in breadcrumb and fried. The oil temperature and the quality of the ingredients are capital to have a perfect arancina. Nowadays, arancine can be found in very different versions – vegan and vegetarian–friendly, but there’s one thing that’ll never change. Only in Palermo, the arancina is female; in the rest of Sicily, it is called «arancino.» A queen is a queen!

Arancina at 'Ke Palle' (Arancine d'Autore) in Via Maqueda.

Tourist Attractions

(Palermo in 6 comprehensive tours)

Palermo is a big city, but it is easy to walk around. Most places of interest are not far from each other. I organized my visit around the city in six tours.

1. Around Quatro Canti.

2. From Giardino Inglese to Quatro Canti , along Via della Liberta and Via Maqueda.

3. From Quatro Canti to Palazzo della Cuba, along Via Vittorio Emanuele and Corso Calatafimi.

4. East of Via Roma (Kalsa, Sant’Erasmo and the port)

5. North of Vittorio Emanuele (Monte di Pieta, Zisa)

6. South of Vittorio Emanuele (Albegheria, Ballaro)

Tour 1

Around 'Quatro Canti'.

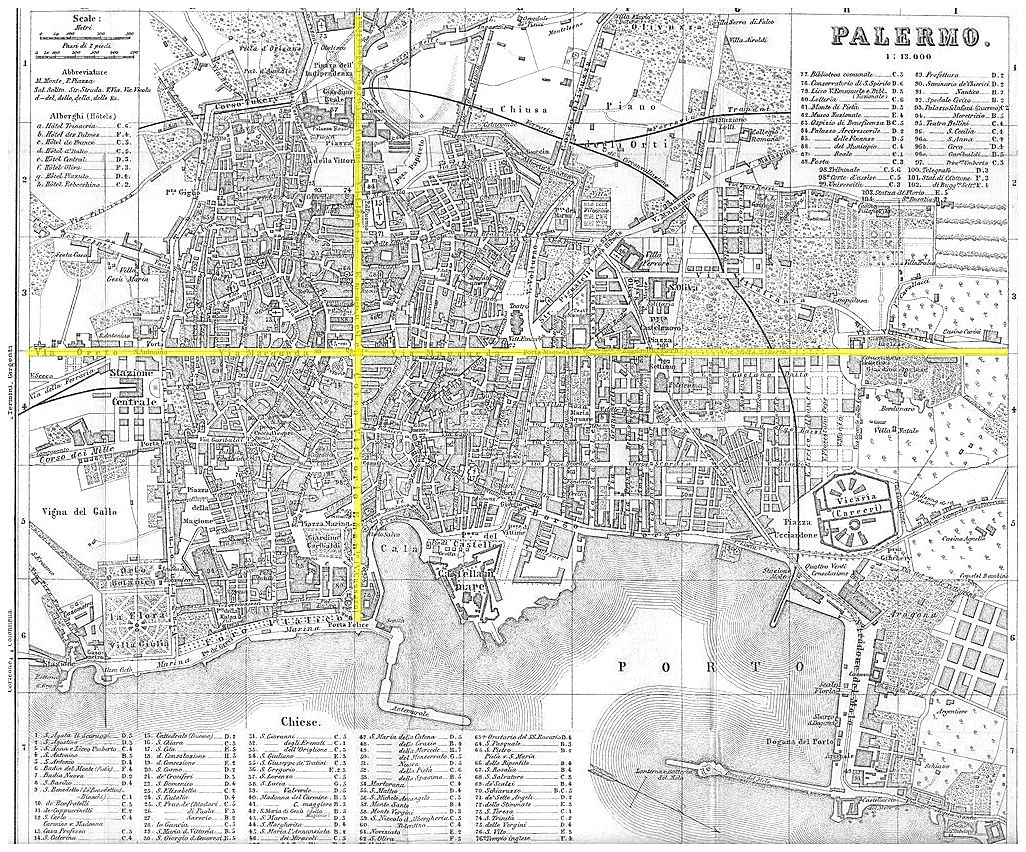

Quatro Canti is the center of the city, as can be cIearly seen in this 1893 map of Palermo.

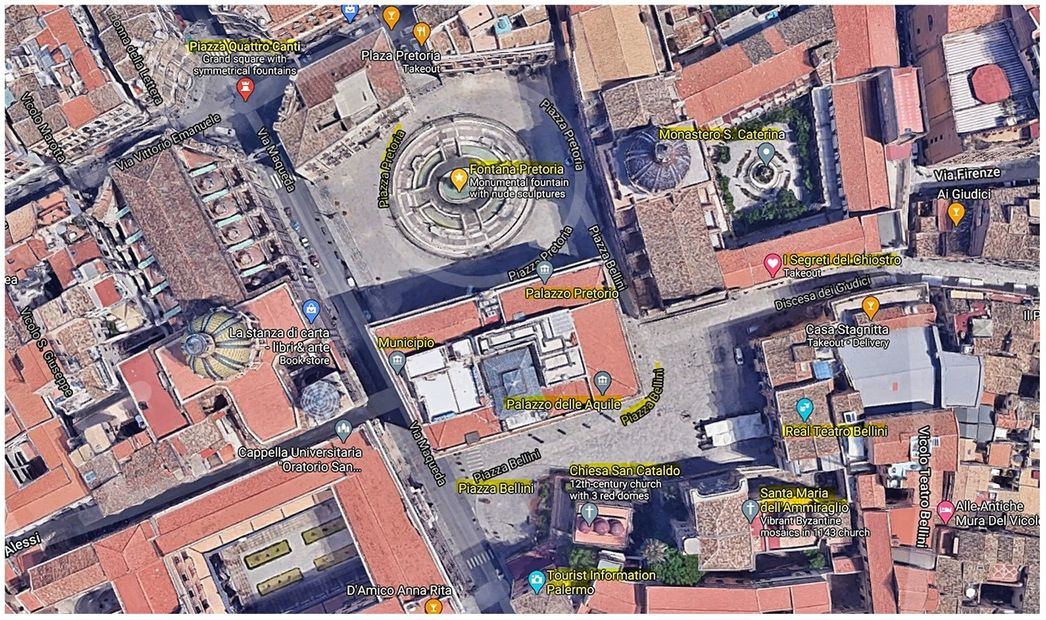

Quattro Canti and the attractions around it.

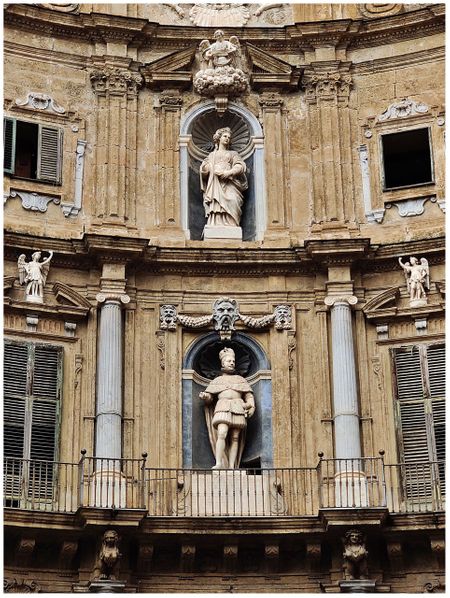

I Quattro Canti

Quattro Canti (“four corners”) is considered the central point in Palermo, making a crossroads between two of the city’s busiest streets, Via Maqueda & Via Vittorio Emanuele. Both roads are pedestrianized at most οf their length.

Quattro Canti.

Quattro Canti.

Quattro Canti in a Xmas night.

More officially known as Piazza Vigliena, the baroque structures around it were built in 1608, featuring four kings, four seasons, four fountains, four palaces, four saints, the meeting point of four neighborhoods, and more.

Quattro Canti is the meeting point for locals and tourists and the best point to start your visit to Palermo. There are many restaurants, cafes and bars around this famous crossroad and the most important places of interest are only some minutes walk away.

Quattro Canti is the meeting point for locals and tourists and the best point to start your visit to Palermo.

Piazza Pretoria

Quattro Canti. Via Vttorio Emanuele (looking west).

Behind the southeastern façade of “Quattro Canti” stands Piazza Pretoria with the huge complex of “Fontana Pretoria.” Fontana Pretoria is nicknamed the “fountain of shame” because of the naked statues surrounding it. These statues represent Greek and Roman mythology characters and add wonder to this fountain. Personally, I find this fountain extremely kitsch! There is an elevated entrance on the fountain's eastern side: get up there for a better picture! This entrance belongs to one of the city's fascinating tourist attractions: the monastery of Santa Caterina D'Alessandria. The entrance to the monastery is on the south, at Piazza Bellini.

Piazza Pretoria seen from the rooftop terraces of Monasterio di Santa Caterina D'Alessandria. The baroque church dominating the centre of the picture is 'Chiesa di San Giuseppe dei Padri Teatini'.

The fountain was built by Francesco Camilliani in the city of Florence in 1554 but was transferred to Palermo in 1574. The fountain was created for the garden of don Luigi de Toledo in Florence. Later, in 1584, the Palazzo di San Clemente was built on this site. The creation of this unusual garden (devoid of palaces) and the fountain was commissioned to the Florentine sculptor Francesco Camilliani. The work was started in 1554. The fountain included 48 statues and was surrounded by a long arbor formed by 90 columns of wood designed by Bartolomeo Ammannati. Giorgio Vasari called the fountain: «fonte stupendissima che non ha pari in Fiorenza nè forse in Italia» («the most wonderful fountain, that is unparalleled in Florence and maybe in all Italy»).

In 1573 the indebted Luigi de Toledo, on the verge of moving to Napoli, sold the fountain to the city of Palermo. In fact, the Senate of Palermo decided to buy the building to place it in the square in front of the Palazzo Pretorio. To make room for the fountain, several buildings were demolished. To transport it, the fountain was disassembled into 644 pieces. On 26 May 1574, the fountain arrived in Palermo, but it arrived incompleted. Some sculptures were damaged during the transport. Others were maybe kept by Luigi de Toledo (probably the statues of two Divinities preserved in the Bargello Museum of Florence and other statues placed in Naples and then in Abadia's garden in the Spanish city of Cáceres). Therefore, in Palermo, some adjustments were necessary. Camillo Camilliani made the work of assembling. In 1581 he completed the work with the help of Michelangelo Naccherino.

A lion decorating Piazza Pretoria. A 1973 Posta Italiana postal stamp depicting Fontana Pretoria (right).

Between the 18th century and 19th century, the fountain was considered a depiction of Palermo's corrupt municipality. Thus, and because of the nudity of the statues, the square became known as "Piazza della Vergogna" (Square of Shame). In 1973, the Italian National Postal Service dedicated a postage stamp to the Fontana Pretoria. In 1998 started the restoration of the fountain, which completed in 2003.

Fontana Pretoria.

Monasterio di Santa Caterina D'Alessandria

Monasterio di Santa Caterina D'Alessandria (The convent* of Saint Cathrine of Alexandria) is one of the highlights of your Palermo experience. From 1311 until 2014, it welcomed nuns of the Dominican order. Since 2017 it has been open to the public, and today it can be visited as a museum of sacred art. Inside, there is a confectionery, where sweets from various Palermo convents are reproduced according to the nuns' ancient recipes. There is an entrance fee to visit the church, the convent, and the rooftop terraces (the combined 10euro fee covers all attractions). The ticket office is located beside the church and can be reached from both the church and the cloister. In the ticket office, note the ruota (wheel) below the counter, used by the cloistered nuns to pass their baked sweet treats to customers, as well as to receive abandoned infants.

(*) unlike other languages, in English, the term monastery is generally used to denote the buildings of a community of monks. In modern usage, convent tends to be applied only to institutions of female monastics (nuns), particularly communities of teaching or nursing religious sisters.

The entrance to the church of Monasterio di Santa Caterina D'Alessandria is located on Piazza Bellini.

Inside the Monasterio di Santa Caterina D'Alessandria (main reception hall).

In 1310 the last will of the wealthy lady aristocrat Benvenuta Mastrangelo determined a convent's foundation under the Dominican Order's direction. The new convent was dedicated to Saint Catherine of Alexandria (Santa Caterina d'Alessandria). It was erected in the area where George of Antioch's old palace, admiral of Roger II of Sicily, stood.

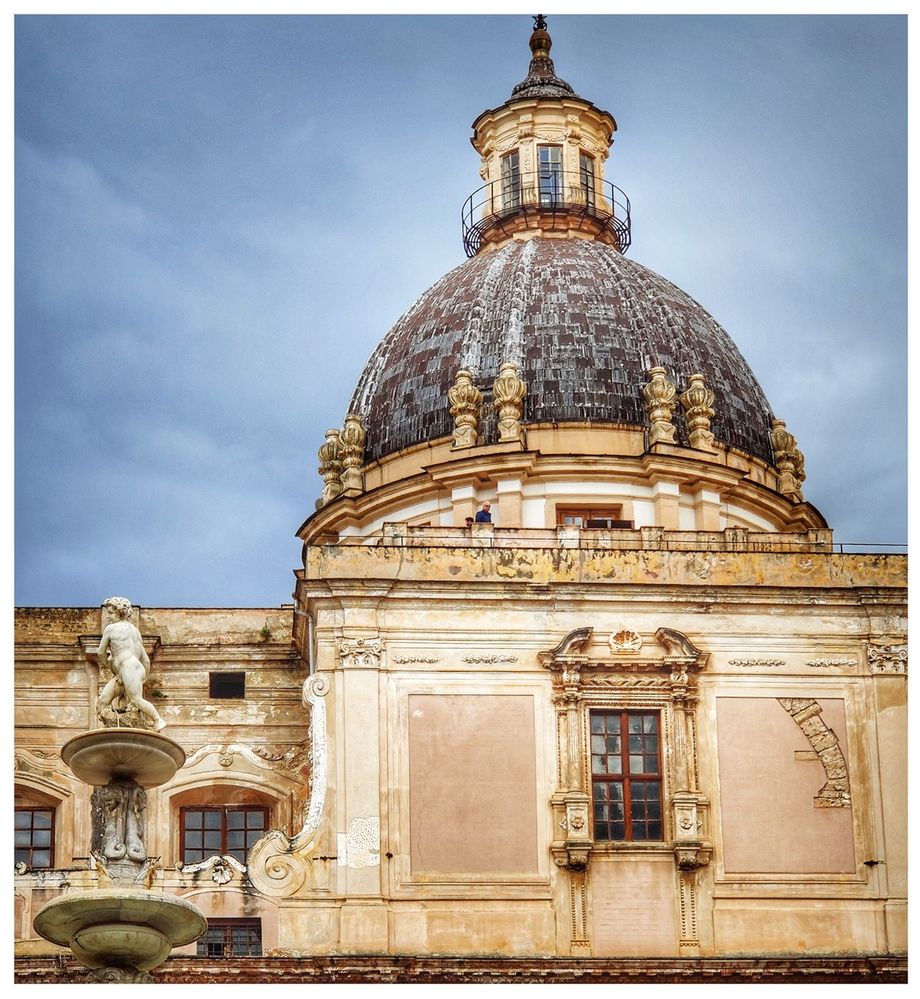

In 1532, due to the increase in the number of nuns, the church of San Matteo was purchased by the convent to enlarge its facilities. The church was small, so between 1566 and 1596, it was rebuilt under the supervision of Mother Prioress Maria del Carretto (Chiesa di Santa Caterina d'Alessandria). The new church was inaugurated on 24 November 1596. For a long time, the architectural project was attributed to Giorgio di Faccio, the architect of another Palermo church, San Giorgio dei Genovesi. However, more recent studies show the involvement of architects like Florentine Francesco Camilliani and the Lombard Antonio Muttone, already engaged in Piazza Pretoria's project. Francesco Ferrigno designed the church's dome. In the seventeenth century, the convent had become one of the most important in the city in terms of wealth and extension and by now occupied an entire block.

The dome of Chiesa di Santa Caterina d'Alessandria (seen from Piazza Pretoria).

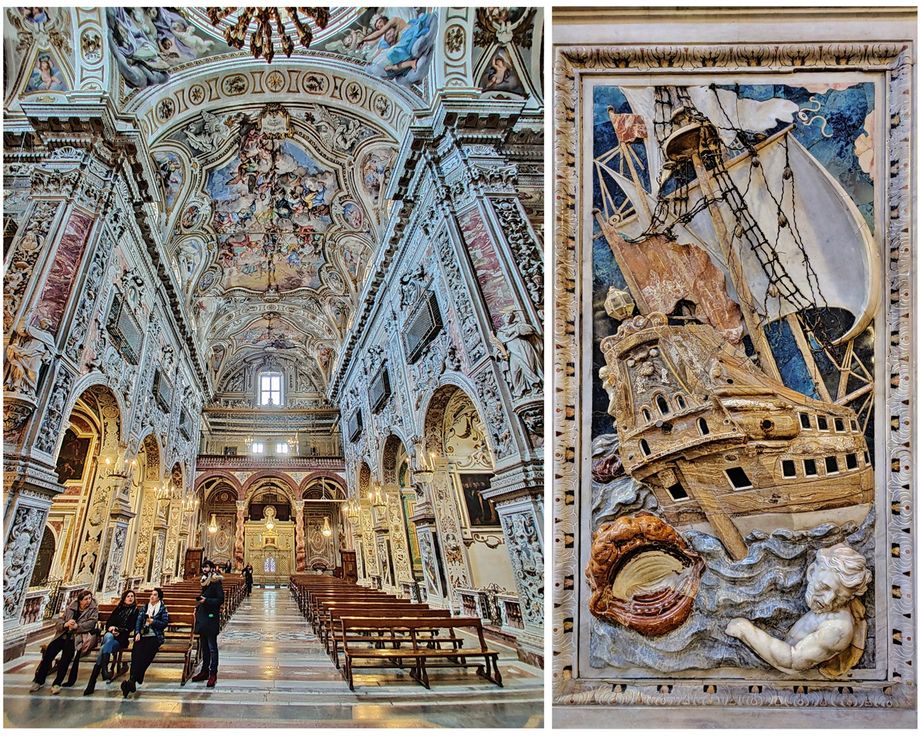

The church's baroque interior harbors work by prolific artists, among them Filippo Randazzo, Vito D'Anna, and Antonello Gagini. Randazzo executed the vault fresco depicting the Triumph of Saint Catherine, while D'Anna created both the Triumph of the Holy Dominicans fresco in the dome and the Allegories of the Four Continents in the dome's pendentives. Andrea Palma's 18th-century altar to St Catherine frames Antonello Gagini's 16th-century sculpture of the saint in the transept. Notable 17th-century paintings decorate the side chapels, among them, The Virgin (second chapel on the left) and The Deposition (first chapel on the right), attributed to Vincenzo Marchese and Giacomo Lo Verdo, students of baroque master Pietro Novelli.

Inside the church of the Monasterio di Santa Caterina D'Alessandria.

The altar of Chiesa di Santa Caterina d'Alessandria.

During the 19th century, the church was damaged on several occasions: during the uprising of 1820-1821, the Sicilian revolution of 1848, the Gancia revolt, and Palermo's insurrection (1860) and the Sette e mezzo revolt (1866). The convent suffered considerable damage due to the Anglo-American bombings of 1943. The last nuns left the convent in 2014, and today it is open to the public. Since 2018 it hosts the exhibition "Sacra et Pretiosa."

The monastic complex wows with its magnificent maiolica cloister, surrounded by unique balconied cells and punctuated by an 18th-century fountain by Sicilian sculptor Ignazio Marabitti. You can see an obelisk (water tower) with the Dominican symbols in one of the corners of the cloister. On the eastern side of the cloister is the medieval prospectus classroom capitulate.

The cloister of the Monasterio di Santa Caterina D'Alessandria.

In the middle of the cloister stands the 18th-century fountain by Sicilian sculptor Ignazio Marabitti. You can see an obelisk (water tower) with the Dominican symbols in the corner behind the fountain.

The obelisk with the Dominican symbols in one of the corners of the cloister (left). The magnificent maiolica cloister is surrounded by unique balconied cells.

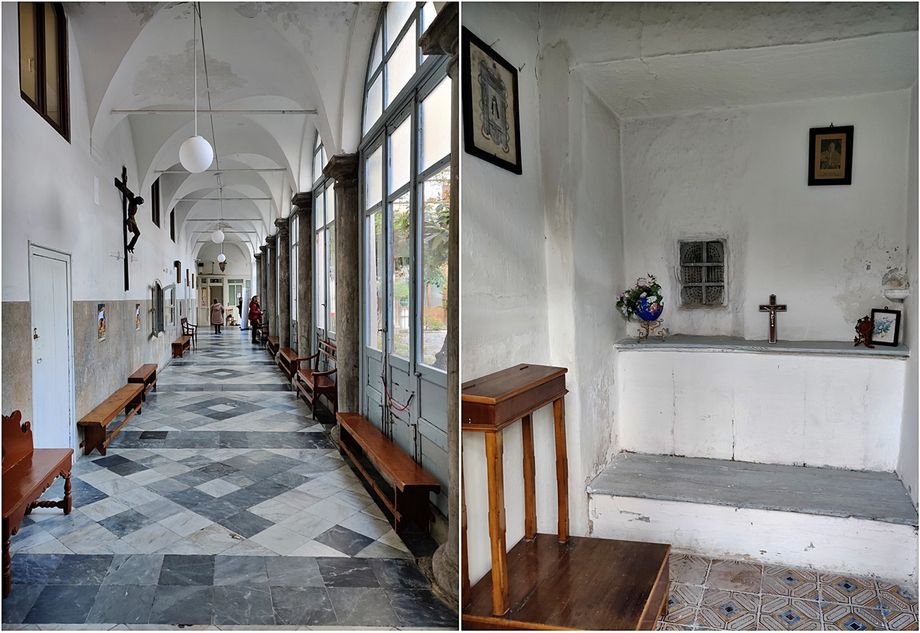

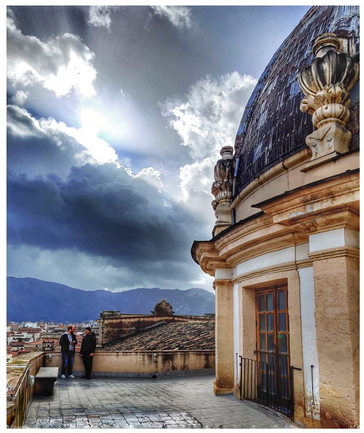

The convent's rooftop terraces offer spectacular 360 ° views of the surrounding piazzas and the city. The terraces were, until 1866, loggias covered and protected by grates: only through these precautions the cloistered nuns could occasionally look out onto the city streets and peek at what was happening in the world they had abandoned.

Grates are placed at several monastery rooms, through which the nuns could watch inside the church, without them being seen from people below. That was the only way to “attend” the masses, as they could not get out of their premises.

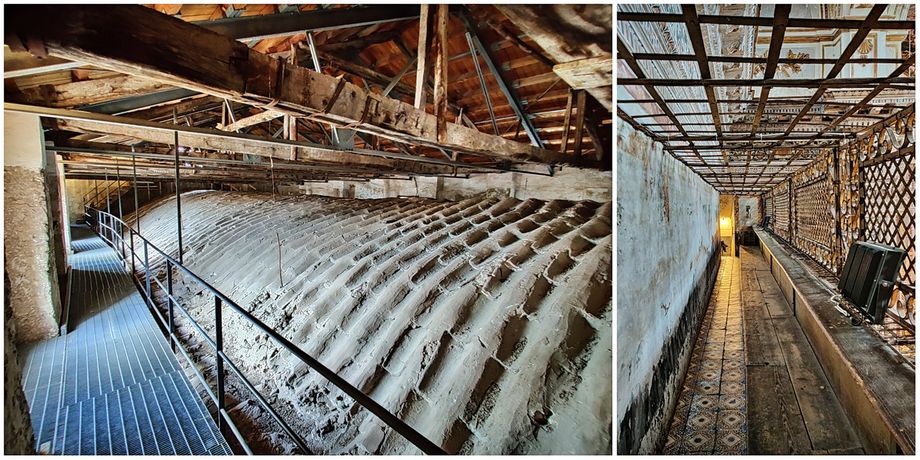

On your way through the monastery to the rooftop terraces, you find yourself walking on catwalks on top of the church’s roof and through its wooden structures. It is a strange feeling like walking on “thin ice,” not for the acrophobic ones. Metal grates are placed at several monastery rooms, through which the nuns could watch inside the church, without them being seen from people below. That was the only way to “attend” the masses, as they could not get out of their premises.

On your way through the monastery to the rooftop terraces, you find yourself walking on catwalks on top of the church’s roof and through its wooden structures. It is a strange feeling like walking on “thin ice,” not for the acrophobic ones.

The convent's rooftop terraces offer spectacular 360 ° views of the city. Here's a view towards the north and Monte Pellegrino.

The convent's rooftop terraces offer spectacular 360 ° views of the city. Here's a view towards the south.

The convent's rooftop terraces offer spectacular 360 ° views of the city. Here's a view towards the west.

While the last nuns moved out in 2014, their baking tradition lives on at the convent's onsite bakery, I Segreti del Chiostro. "The secrets of the cloister" is a project to rediscover and enhance the ancient traditions of convent pastry: an important material heritage that cannot be lost and that must be handed down to future generations.

The apothecary or confectionery of Santa Caterina was the convent's place in charge of making biscuits, filled pasticciotti, pancakes, preserves, and so on. The sale of sweets represented an essential source of income for the convent's survival.

Today, the shop offers a variety of must eat pastries—free admission from Piazza Bellini.

I Segreti del Chiostro pastry shop inside Monasterio di Santa Caterina D'Alessandria.

A variety of 'I Segreti del Chiostro' pastries you have to taste.

A variety of 'I Segreti del Chiostro' pastries.

Santa Caterina D'alessandria

Santa Caterina D'Alessandria is a martyr of the 3-4th century who lived in Egypt. It is represented according to traditional iconography with the crown, a symbol of royalty; the palm, symbol of martyrdom and the wheel, symbol of the torture suffered. Catherine embodies the ideal of the virgin consecrated to Christ (mystical wedding).

The worship of Caterina spreads in Sicily during the Spanish domination. The convent in Palermo possessed a polyptych in which Catherine was represented together with other saints, but alongside the traditional symbols, the disc with the seven liberal arts was depicted. Today the polyptych is exhibited at the Abatellis museum.

According to tradition, Catherine was a beautiful young Egyptian. She was King Costa's daughter, who left her orphaned very young and was educated from childhood in the liberal arts. Catherine was asked in marriage by many important men, but she had in a dream the vision of the smiling Child Jesus, in the arms of Mary. Jesus put the ring on her finger, making her his wife, and for this reason, she was taken as an example to follow for the nuns. The anniversary of Saint Catherine of Alexandria falls on November 25.

The tryptich of the Mystical marriage of Saint Catherine (Lorenzo Salimbeni, 1400). In the central panel, an aristocratic saint (Catherine was after all a princess, in fact she wears the crown) who is receiving the ring of the mystical marriage from the smiling Child Jesus, in the arms of Mary. Mary looks impassively elsewhere, but her hands are occupied in the affectionate care of the Child, caressing his head and adjusting the edge of the cloth that wraps him on his shoulder. The scene is set in a heavenly garden, with a great variety of roses (Marian flower), depicted with extreme attention to naturalistic detail. But the most interesting part is the swirling play of the lines that weave the drapery, with the strides of the flaps sometimes wide, sometimes nervously curled. Everything is highlighted by the unreal, bright and iridescent colors. In the side compartments, full-length, the Saints Simon and Judas Taddeo.

Piazza Bellini

Besides the baroque church and the convent of Santa Caterina, in the perimeter of Piazza Bellini are located two buildings dating back to the era of Norman Sicily: the churches of Martorana and San Cataldo (both are UNESCO World Heritage Sites as part of "Arab-Norman Palermo and the Cathedral Churches of Cefalù and Monreale"). In the square are also located the Bellini Theatre and the rear facade of Palazzo Pretorio (Palazzo delle Aquile), headquarters of the Comune of Palermo. Moreover, in the square, some ruins of Punic walls are visible. Near the square, in Via Maqueda, has its location the Faculty of Jurisprudence. There is a Tourist Information office next to San Cataldo's Church, but do not expect much! We are in Italy, after all!

Piazza Bellini and Chiesa di Santa Caterina D'Alessandria. A glimpse Teatro Bellini can be seen on the right.

Santa Maria dell'Ammiraglio

The Church of St. Mary of the Admiral (Santa Maria dell'Ammiraglio), also called Martorana, is the Parish of San Nicolò dei Greci's seat. The church is a Co-cathedral to the Eparchy of Piana degli Albanesi of the Italo-Albanian Catholic Church, a diocese that includes the Italo-Albanian communities in Sicily who officiate the liturgy according to the Byzantine Rite in the Ancient Greek language and Albanian language.

The Church bears witness to the Eastern religious and artistic culture still present in Italy today. This influence has left considerable traces in the painting of icons, in the religious rite, in the parish language, in the traditional customs of some Albanian colonies in the province of Palermo. The community is part of the Catholic Church but follows the ritual and spiritual traditions that primarily share it with the Orthodox Church.

The north facade of Santa Maria dell'Ammiraglio on Piazza Bellini. The original church can be seen on the left, while the newer structure with the blueish Baroque façade and the campanile is seen on the right.

Albanians in Sicily

Albanians were tribes living in the Caucasus and had converted to Christianity, like most peoples in the region. In 724, the Arabs occupied Albania and imposed Islam on it. In 730, Khazar prince Bariel Bardzil conquers Albania. As an opponent of Islam, he commits pogroms against Islamized Albanians. Some of the Islamized Albanians, to escape, fled to the Arab countries of the Arab Caliphate. In the 8th century, the Arab Caliphate, which extends to the Mediterranean, conquered Sicily and southern Italy. In these areas, to strengthen defense and Islam, the Caliphate transported and colonized Albanians. In 980, the Byzantines, led by General George Maniakis, recaptured Sicily and southern Italy, and the Albanians become Christians again. This justifies the existence of Albania communities in Sicily and South Italy. These communities were further contributed by the Christian Albanian exiles who took refuge in the area from the 15th century under the pressure of Turkish-Ottoman persecutions in the Balkans.

Piazza Bellini seen from Monasterio di Santa Caterina. Teatro Bellini is on the left and Santa Maria dell'Ammiraglio in the middle.

The name Ammiraglio ("admiral") derives from the founder of the church, the Syrian Christian admiral and principal minister of King Roger II of Sicily, George of Antioch. The foundation charter of the church (which was initially Eastern Orthodox), in ancient Greek and Arabic, is preserved and dates to 1143; construction may already have begun at this point. The church had certainly been completed by the death of George in 1151, and he and his wife were interred in the narthex. In 1184 the Arab traveller Ibn Jubayr visited the church, and later devoted a significant portion of his description of Palermo to its praise, describing it as "the most beautiful monument in the world." After the Sicilian Vespers of 1282 the island's nobility gathered in the church for a meeting that resulted in the Sicilian crown being offered to Peter III of Aragon.

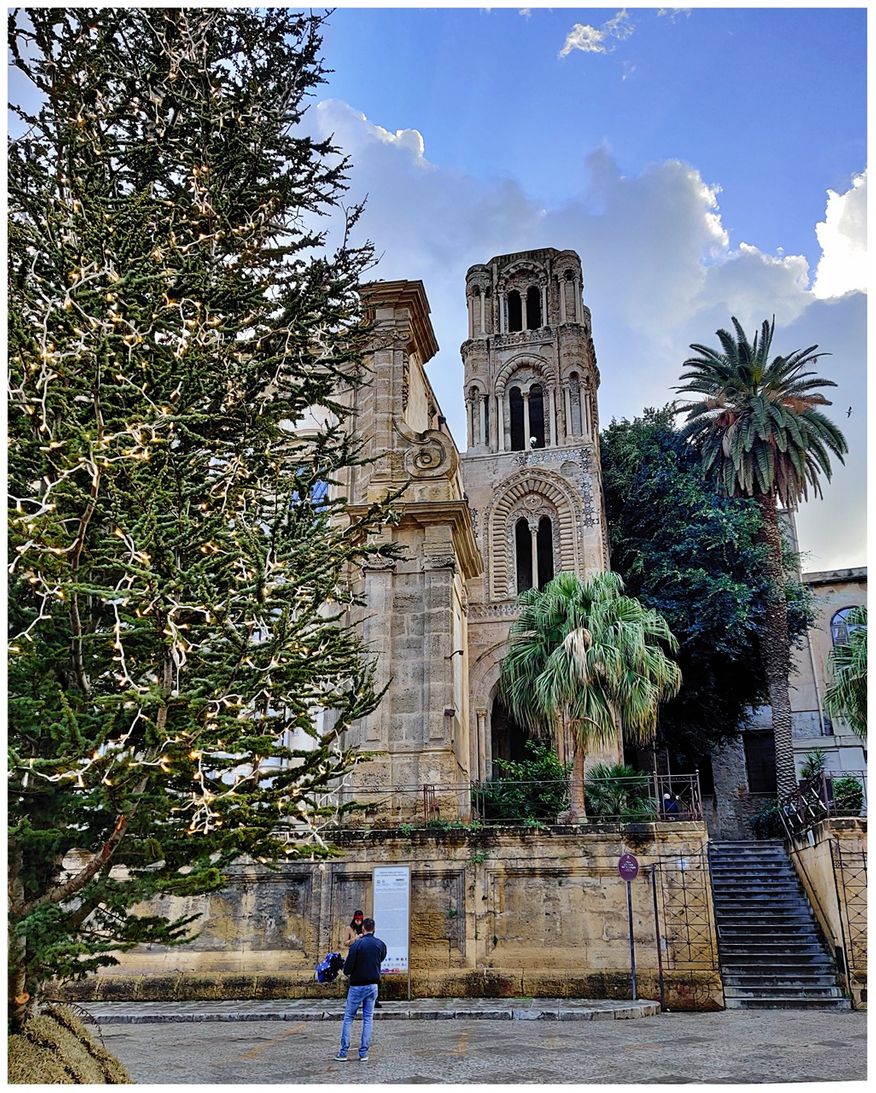

The campanile of Santa Maria dell'Ammiraglio still serves as the main entrance to the church.

In 1193–94, a Benedictine nuns' convent was founded on the adjacent property by Eloisa Martorana. In 1433–34, under the rule of King Alfonso of Aragon, this convent absorbed the church, which has since then been commonly known as La Martorana. The nuns extensively modified the church between the 16th century and the 18th century, making major changes to the structure and the interior decoration.

The nuns of the Martorana were famous for their molded marzipan, which they made in the form of various fruits. Although the convent no longer exists, 'Frutta di Martorana' are still one of Palermo's most famous and distinctive foodstuffs.

In 1937 the church returned to the Byzantine rite with the Albanian community present in Palermo. Today, it is used by the Italo-Albanian Catholic Church for their services and shares cathedral status with the church cathedral of San Demetrio Megalomartire in Piana degli Albanesi.

The original church was built in the form of a compact cross-in-square ("Greek cross plan"), a common variation on the standard middle Byzantine church type. The three apses in the east adjoin directly on the naos, instead of being separated by an additional bay, as was usual in contemporary Byzantine architecture in the Balkans and Asia Minor. In the first century of its existence, the church was expanded in three distinct phases; first through the addition of a narthex to house the tombs of George of Antioch and his wife; next through the addition of a forehall; and finally through the construction of a centrally-aligned campanile at the west. The campanile, which is richly decorated with three orders of arches and lodges with mullioned windows, still serves as the main entrance to the church. Significant later additions to the church include the Baroque façade, which today faces onto the piazza. In the late 19th century, historically-minded restorers attempted to return the church to its original state, although many Baroque modifications remain.

Certain elements of the original church, mainly its exterior decoration, show Islamic architecture's influence on Norman Sicily's culture. A frieze bearing a dedicatory inscription runs along the top of the exterior walls; although its text is in Greek, its architectural form references the Islamic architecture of North Africa. The recessed niches on the exterior walls are likewise derived from the Islamic architectural tradition. In the interior, a series of wooden beams at the dome's base bear a painted inscription in Arabic; the text is derived from the Christian liturgy (the Epinikios Hymn and the Great Doxology). The church also boasted an elaborate pair of carved wooden doors, today installed in the south façade of the western extension, which relate strongly to the artistic traditions of Fatimid North Africa. On account of these "Arabic" elements, the Martorana has been compared with its Palermitan contemporary, the Cappella Palatina, which exhibits a similar hybrid of Byzantine and Islamic forms.

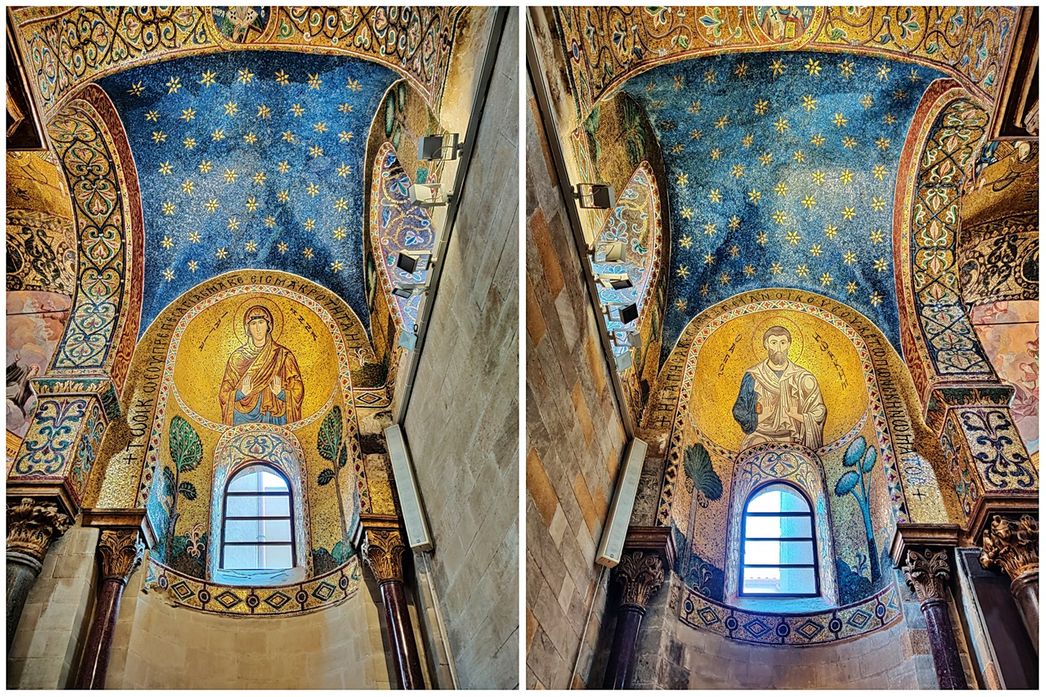

Inside the original (Byzantine) part of Santa Maria dell'Ammiraglio. The church is renowned for its spectacular interior, dominated by a series of 12th-century mosaics executed by Byzantine craftsmen.

The church is renowned for its spectacular interior, dominated by a series of 12th-century mosaics executed by Byzantine craftsmen. The mosaics show many iconographic and formal similarities to the roughly contemporary programs in the Cappella Palatina, in Monreale Cathedral, and in Cefalù Cathedral, although a distinct atelier probably executed them.

Inside the original (Byzantine) part of Santa Maria dell'Ammiraglio. The spectacular interior is dominated by a series of 12th-century mosaics executed by Byzantine craftsmen. Here we see Virgin Mary's parents: Sant' Anna (left) and Santa Ioakeim (right).

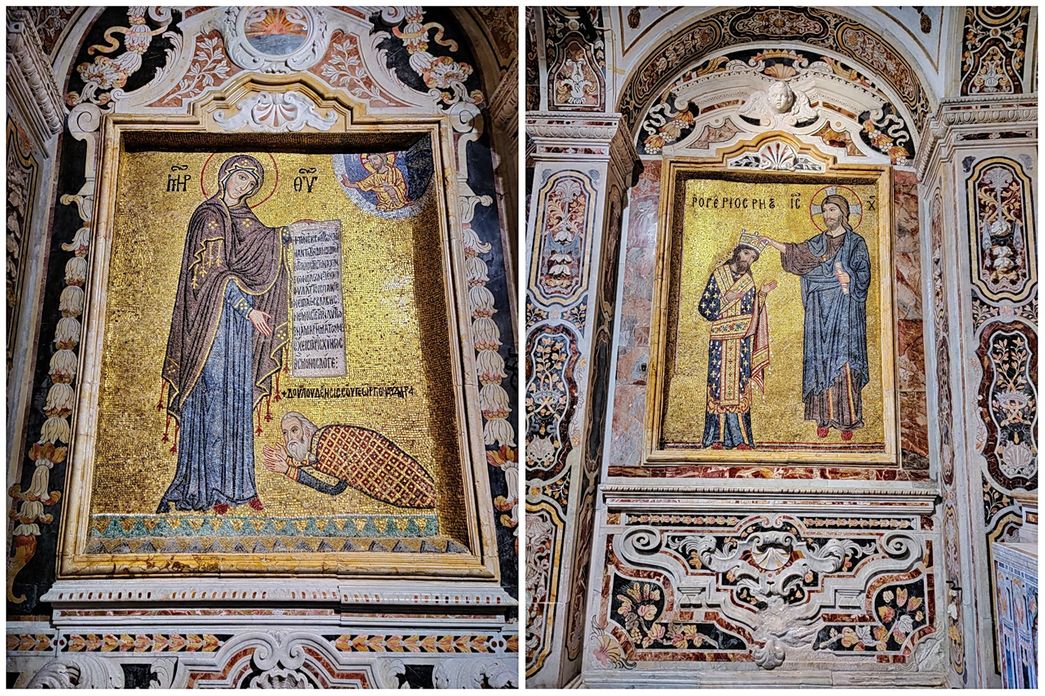

The walls display two mosaics taken from the original Norman façade, depicting King Roger II, George of Antioch's lord, receiving the crown of Sicily from Jesus, and, on the northern side of the aisle, George himself, at the feet of the Virgin. The depiction of Roger was highly significant in terms of its iconography. In Western Christian tradition, kings were customarily crowned by the Pope or his representatives; however, Roger is shown in Byzantine dress being crowned by Jesus in the Byzantine fashion. Roger was renowned for presenting himself as an emperor during his reign, being addressed as basileus ("king" in ancient Greek). The mosaic of the crowning of Roger carries a Latin inscription written in ancient Greek characters (Rogerios Rex ΡΟΓΕΡΙΟΣ ΡΗΞ "King Roger").

The walls display two mosaics taken from the original Norman façade, depicting King Roger II, George of Antioch's lord, receiving the crown of Sicily from Jesus (right), and, on the northern side of the aisle, George himself, at the feet of the Virgin (left).

The nave dome is occupied by the traditional byzantine image of Christ Pantokrator surrounded by the archangels St Michael, St Gabriel, St Raphael, and St Uriel. The register below depicts the Old Testament's eight prophets and, in the pendentives, the four evangelists of the New Testament. The nave vault depicts the Nativity and the Death of the Virgin.

The newer part of the church is decorated with later frescoes of comparatively little artistic significance. In the middle part of the walls, the frescoes are from the 18th century, attributed to Guglielmo Borremans.

Santa Maria dell'Ammiraglio. The Byzantine dome (left) and the newer baroque dome (right).

Chiesa San Cataldo

Chiesa San Cataldo (Church of San Cataldo) was erected in 1154 as a notable example of the Arab-Norman architecture, which flourished in Sicily under Norman rule on the island. The church is annexed to that of Santa Maria dell'Ammiraglio.

Since the 1930s, it belongs to the Order of the Holy Sepulchre. Founded around 1160 by admiral Majone di Bari in the 18th century, the church was used as a post office. In the 19th century, it was restored and brought back to a form more similar to the original Mediaeval edifice.

The north facade of Chiesa San Cataldo on Piazza Bellini. The ceiling has three characteristics red, bulge domes (cubole).

It has a rectangular plan with blind arches, partially occupied by windows. The ceiling has three characteristics red, bulge domes (cubole), and Arab-style merlons. The church provides a typical example of Arab-Norman architecture, which is unique to Sicily. The church's plan shows the predilection of the Normans for simple and severe forms derived from their military formation. Moreover, the building shows how international the language of Norman architecture was at the time, as the vocabulary which marks parts of the church, like the bell tower, can be tracked down in coeval buildings like the cathedral of Laon and the Abbaye aux Dames in Caen, both in Northern France or the cathedral of Durham in England. At the same time, the church shows features shared by Islamic and Byzantine architecture, such as the preference for cubic forms, the blind arches that articulate the church's external walls, and the typical spherical red domes on the roof.

The three domes of Chiesa San Cataldo.

The interior has a nave with two aisles. The naked walls are faced by spolia columns with Byzantine-style arcades. The pavement is the original one and has a splendid mosaic decoration. Also original is the main altar.

The old City Wall can be seen running underneath the Church.

Inside Chiesa San Cataldo. The naked walls are faced by spolia columns with Byzantine-style arcades. The main altar can be seen on the left.

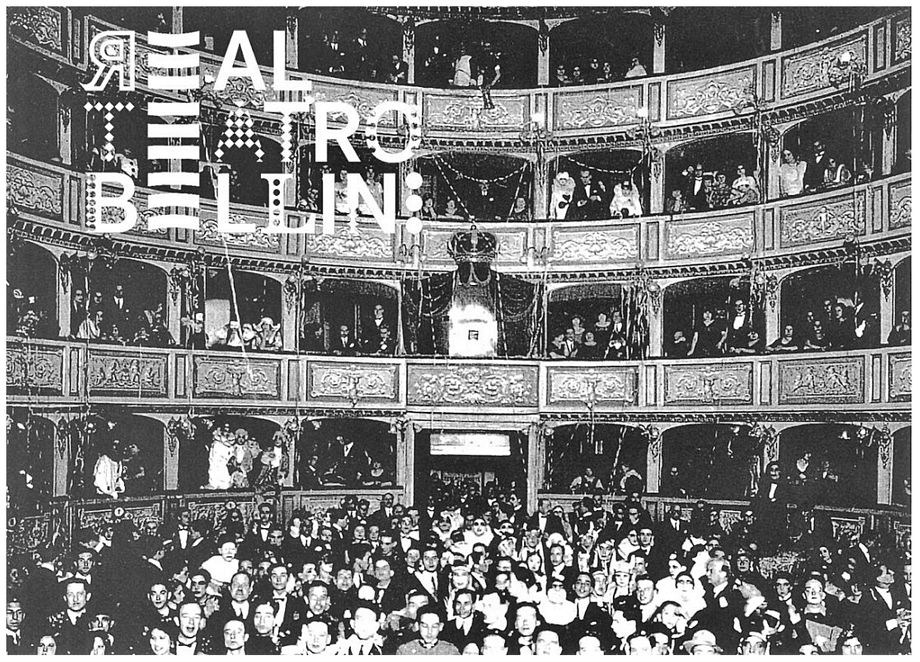

Teatro Bellini

The Real Teatro Bellini or Regio Teatro Carolino started its history in 1726 when at this place inaugurated a large Italian-style theater called Teatro Santa Lucia. It took its name from the Marquises Valguarnera di Santa Lucia and was built entirely of wood. It could accommodate 500 spectators and was considered the most important theater in the city of Palermo until the mid-nineteenth century. When the Neapolitan court moved to Palermo, with the revolution of 1799, Queen Maria Carolina of Habsburg-Lorraine became a frequented, and the theater in her honor became Real Teatro Carolino. It underwent several renovations, the first in 1808 by Nicolò Puglia and a subsequent one in 1840, in which the facade of the building was rebuilt by the architect Rosario Torregrossa Palazzotto. On 7 January 1826, the world premiere of ‘Alahor in Granata’ by Gaetano Donizetti takes place. In 1848 the theater was named after the famous Catania composer Vincenzo Bellini. Before the construction of the two great theaters of the late nineteenth century, the Teatro Massimo and the Politeama, the "Real Teatro Bellini" together with the Santa Cecilia theater were the only opera houses in the city and among the most important in the country.

The facade of Real Teatro Bellini on Piazza Bellini.

From 1907, the theater continued to function for variety shows. In 1943, it was requisitioned by the US military during Operation Husky and used as a movie theater for soldiers. Until the early sixties, the theater continued to be used as a cinema. In 1964 the building was damaged by a fire. Later it was rebuilt and returned to its original function in 1980. After a few years, it definitively ceased its activity, and the last years had been open to the public only for occasional use. Finally, in April 2019, the Terradamare cooperative opened the theater to visits with the desire to relaunch the shows.

The old glory of Real Teatro Bellini.